Like many of our tribe, I have managed to collect for myself a “voluntary” family. I’ve been blessed to include in it several “real” relatives, as well as dear friends. But as most of my relatives live thousands of miles away, it is crucial friends who have made my life, in recent years, the most worth living. One straight ally, in particular, respected the dignity of everyone she knew. While we should certainly do this, too, it is especially powerful when lived out by people who stand by us – even when they don’t have to.

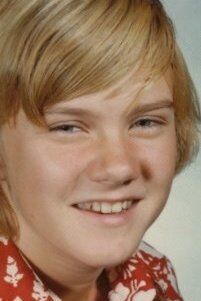

Mary Lou was the first person I came out to. She was a retired hospital nurse who worked as a therapist through her Catholic parish, to which I then belonged. Every week she had a “Drop-in Group” for people who needed therapy and couldn’t afford a high-priced downtown doctor. She also saw me on a one-to-one basis, charging me nothing for the priceless assistance she gave me.

At the time Mary Lou was seeing me in her study at home once a week, my mother was wasting away of Alzheimer’s dementia and in the process of forgetting who I was. Mary Lou was a mother to me at a time when I desperately needed one. Her death hit me harder than that of my own mom.

We testify to the light when we stand up and do the right thing, regardless of whether we get any applause for it. Mary Lou didn’t let the Catholic Church’s disapproval of gays get in her way. She cared for us as fellow children of God, extending the hand of friendship to us anyway.

In the last issue, I spoke of the compassion that comes from shared suffering – empathy. But there is much to say about compassion for “the other.” It is harder, by far, to stir within us, but in a world filled with “others,” it is vastly more important. It may even make the difference between a world that survives and a world in which we end up destroying each other.

No one forces God to love us. We are entirely dependent upon God’s goodness. God’s good – and always will be – because that’s Who God is. As “His” Name, as given to Moses at the burning bush, implies, “I am who I am.” Or, translated more correctly, “I will be who I will be.”

Those who are good to those they don’t have to be good to testify to the light of God. There’s no “what’s in it for me?” attitude for them. The less self-interested their love for others happens to be, the more God-like it is.

God weeps with us when we cry. But God doesn’t have to do that. No one would punish “Him” if “He” stonily hid away and left us to weep all alone.

We make much – and rightly so – of the fact that Jesus was born a human being, in this human world, to live, and laugh, and cry, and suffer and die alongside of us. But there were other choices He could have made along the way.

He was, like each of us, rooted in a particular time and place. He could have been one of those Jewish men who simply thanked God every morning He had not been born a woman, disdained contact with all gentiles, tax-collectors and other “sinners” and spent His life congratulating Himself on how He had “earned” every blessing because of His superior godliness.

Instead, He befriended women (shocking even His own disciples by so much as talking to one), even going so far as to welcome them into His family of disciples. He healed the servant of the centurion – believed, by many scholars, to have been the man’s male lover. He reached out to and welcomed tax-collectors and sinners of every sort, and declared that there would be gentiles in Heaven.

It is generally assumed that Jesus’ carpenter family was poor. But carpenters were actually the master builders of their day, and many were fabulously wealthy. Joseph of Nazareth was, quite possibly, more like Frank Lloyd Wright than like Pa Walton. Jesus may have had the best of everything as He was growing up. We’ll never know just what He gave up when He chose to become an itinerant preacher, trusting in nothing but the providence of God.

I became a Catholic in my twenties, right after graduating from a Southern Baptist University and reeling from the culture-shock of it. I was raised in a liberal mainline church, and after my exposure to the opposite end of the Christian spectrum I sought a balance. I recognize now that my Catholic “conversion” was merely part of the romantic fervor of idealistic youth.

I had already come to the belief that I was probably bisexual – a frequent way-station, I have since learned, for young gays and lesbians searching to make sense of their sexuality. And I was determined, for the sake of my faith, to either find a man I was capable of loving and marry him or else become a nun. Protestants couldn’t do that; Lutheran and Episcopalian nuns do exist, but these days they’re even rarer than the Catholic ones.

I was also attracted to Catholicism by its broadness. I was always a “broad” Protestant (or, as one of my more waggish gay male friends puts it, “a Protestant broad”). I felt that God was too big to be confined by narrow human ideologies, and that “He” deserved a church big enough to do “Him” justice. Pre-Papa Razzi hysteria, that’s exactly what the Church of Rome was.

The tragedy of what has happened to it since is that, in less than ten years’ time, it has gone from being a patchwork quilt of both the wonderful and the terrible to being horribly rent asunder by terror. Its powers-that-be – who keep a death-grip on its very life – seem no longer willing to trust in the goodness of God. The boast of devout Catholics has always been that the Holy Spirit guides them, but they have deposed the Third Person of the Godhead in favor of those who claim (increasingly incredibly) to speak for “Him.”

Mary Lou was a typical broad and generous Catholic. She took to heart what Jesus meant when He charged His followers to take the gospel to the world.

Psychotherapy is very much an investigation of the “other.” Therapists, at least in theory, must be sane and healthy. Their clients very often are not. They must be able to relate to them sensitively and compassionately no matter how bizarre, ugly or frightening revelations made from the couch may be.

God as the Other is an idea frequently misunderstood by bigots. They do not get that even though there is a profound element of “other-ness” in God, God nonetheless relates even more intimately with each and every one of us than we do to ourselves.

Showing forth the great, grand, generous broadness of God testifies to the Light. We do that by transcending our other-ness and sharing the burdens even of those with whom our own, narrow experience has not taught us to relate. Nobody I have ever known did that better than Mary Lou.

We are asking straights, right now, to do that in a big way. It would be a tragedy if we did not recognize the light of God in it. Those among us who despair of God, claiming that “He” has abandoned us, are looking for God in the wrong places. For good or for ill, God has chosen to make the primary vehicle for “His” love, in this world, the way we relate to one another. Without an appreciation for the necessity of looking beyond our petty differences, and seeing the glimmer of God’s love in the other, the light of God goes dark upon the earth.

Again, God is the Ultimate Other. We make much of how we must see God in one another, but it is all too easy to make an idolatry of that. We depend too much on what other people, claiming to speak for God, have to tell us about “Him.” When that light goes dark in others, God has also blessed us with the ability – and, indeed, the responsibility – to rekindle it. People like Mary Lou are doing that every day, and in every way they can.

She helped me to be able to accept myself – straight, bisexual or gay. She was the first to help me recognize that God still abides with me, and that God will never abandon me. When she succumbed to liver cancer, a year before my father passed away and three years before my mother, one of God’s lights in this world was extinguished. But God lives on in a growing number of others who love us, and who are increasingly willing to take a stand beside us. I am determined that it will live on in me, too.

A self-described “Libertarian Episcopalian lesbian,” freelance writer and the author of Good Clowns, a young adult novel published in 2018, Lori Heine published a blog called Born on 9-11 and was a frequent contributor to the website Liberty Unbound. A native of Phoenix, Ariz., she graduated from Grand Canyon University in 1988 and spent much of her life in the insurance industry before turning full-time to writing as a freelancer, blogger and author.