Every Black History Month, there is always a tribute to the Black church and its gospel music. The contribution of LGBTQ+ singers to the canon of gospel music, however, is never front and center in celebration of its history.

Every churchgoer — straight and gay — knows the inimitable style and flair LGBTQ+ singers bring, which have long been part and parcel of gospel music. Moreover, what would gospel music be without the boys in the choir loft and gay church musicians?

There is an undeniable queerness to gospel music, a particular interpretation, and expressiveness by LGBTQ+ people — churched and unchurched. As repressive as the Black church is around openly LGBTQ+ people, many of us nonetheless are drawn to its gospel music.

“It’s Black folks’ prayer and lamentation. It’s our language and expression as a people that cannot be taken away. It speaks to times of great joy and sorrow. It mirrors my breath and the beating of my heart. It is soul-stirring, and a meditation with your spirit with whoever and whatever is your God,” said Gary Bailey, waxing poetic. Bailey is a professor of practice and assistant dean for community engagement and social justice at the Simmons University School of Social Work and is a member of Union United Methodist Church, the first open and affirming Black church in New England.

The Black church applauds its LGBTQ+ congregants in the choir pews, yet excoriates us from the pulpits. It pimps our talent yet damns our souls with the theological qualifier of “love the sinner, but hate the sin.” Our connections and contributions to the larger Black religious cosmos are desecrated every time homophobic pronouncements go unchecked in these holy places of worship. However, our pull to gospel music is seen as a calling, a distinctive gift to the church, and an expression of queer pain and hardship.

For Charles Evans, former vice president of Cape Cod Pride, who with his spouse, Paul Glass, is program coordinator for the LGBT Elders of Color at the Multicultural AIDS Coalition, “Gospel music is tied to suffering, black suffering and certainly black gay suffering. It communicates our trials and tribulations through song that a better day will come.”

Donell Patterson, chair of the Gospel Music department at the New England Conservatory’s Preparatory School, told me his “entire life has been gospel music,” and he has the resume to prove it. Patterson, who conducts three renowned gospel choirs in the Boston Area, said he has observed through the years that some Black church denominations are queerer than others. “Those denominations are more open to gays without announcing it, because of its liturgy and organizational structure like Pentecostal churches.”

The Church of God in Christ (COGIC) is the largest Black and Pentecostal church in the United States. Many of the gospel music industry’s mega-stars are from COGIC. The church, however, is conflicted with itself. These Black gay male mega-stars are always forced to go back into the closet, publicly denouncing their sexual orientation at the church’s annual convocation.

Toxic masculinity contributed to the early years of AIDS, ravaging the gospel industry. The effects of AIDS were widely discussed but rarely publicly acknowledged until the death of James Cleveland, the King of Gospel, in 1991. Cleveland was influential in bringing gay men into the industry. He was a fixture at gay parties in cities he toured, and it was an open secret. However, the most devastating news following Cleveland’s death was when a male member of Cleveland’s choir sued his estate, alleging he contracted HIV during their five-year sexual relationship.

Homophobia and hypermasculinity are rebuked by many openly gay men in gospel music. They see gospel music as a complex welcome space, allowing enough wiggle room to be themselves.

“Gospel music allows you to emote where you can be openly expressive in public with your emotions that you can’t be with your sexuality. In gospel music, you don’t have to suppress either,” Glass said. “Women and gay men can allow the music to take them where (heterosexuals) cannot go.”

For me, gospel music is an embodied musical extravaganza. It reminds me that our bodies are our temples, housing the most sacred and scariest truth about us: Our sexuality.

Through gospel music, I learned that sexuality is an essential part of being human. It is an expression of who we are, a language, and a means to communicate our spiritual need for intimate communion — human and divine.

When we embrace the Christian mind-body dualism, we lose our bodies, sexualities, and spirit. Gospel music helps me not to forget that our sexuality is a spiritual site of revelation, an intimation of the holy unavailable in any other experience, and a source of our capacity for transcendence. However, the church and school truncate that ability to experience an embodied spirituality and homophobic peers.

Gospel music is theater and dramatics rolled up in song. With its overtly gay overtones, gospel music is in the DNA of both Black sacred and secular cultures.

It cannot be overlooked in its influence in Aretha Franklin’s songs, Little Richard’s flamboyant performances, Alvin Ailey’s signature dance piece “Revelations,” or the public fire and brimstone exhortations of James Baldwin, whether at the pulpit or in his writings.

“You can’t listen to them and not hear the gospel influence or hear the music of the church in them,” Bailey said. “And, as for Black gay men — well, it allows us to be peacocks with our multicolored feathers on display.

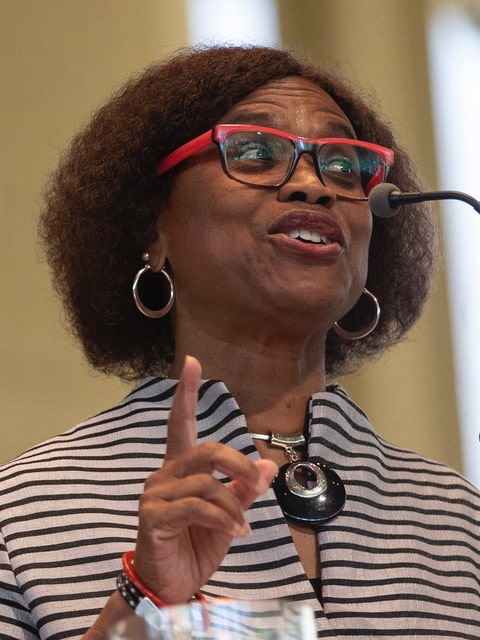

Public theologian, syndicated columnist and radio host Rev. Irene Monroe is a founder and member emeritus of several national LBGTQ+ black and religious organizations and served as the National Religious Coordinator of the African American Roundtable at the Center for LGBTQ and Religion Studies in Religion at Pacific School of Religion. A graduate of Wellesley College and Union Theological Seminary, she served as a pastor in New Jersey before studying for her doctorate as a Ford Fellow at Harvard Divinity School and serving as the head teaching fellow of the Rev. Peter Gomes at Memorial Church. She has taught at Harvard, Andover Newton Theological Seminary, Episcopal Divinity School and the University of New Hampshire. Her papers are at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College’s Research Library on the History of Women in America.