In the Name of God, Abba, Baba, DaDa, Father, Son, and Mother Spirit, AMEN

Abba or ab·ba [ab-uh], New Testament: An Aramaic word for father, used by Jesus and Paul to address God in a relation of personal intimacy.

Once when Jesus was praying in private and his disciples were with him, he asked them, “Who do the crowds say I am?” (Luke 9:18 NIV)

Doesn’t it do your heart good to know, that while we might not want it as the central question of our lives, it’s perfectly all right — indeed perfectly natural — so natural that our Lord Himself asks it: “What do other people think about me?”

I’m a data queen. I keep up with over 3,000 birthdays a year. I post lists galore to the web — a list of over 700 lesbigay scholars and their email addresses, a list of the authors of all the websites at Rutgers University, a list of all living Episcopal bishops and their spouses. I assure you that few things can get you into more trouble than getting a person’s name wrong.

At Rutgers we are exploring more efficient ways to use our electronic networks to communicate with students, faculty and staff. We are a big operation — over 48,000 students — and we consume numerous trees a year in communication that we could do more efficiently through the email which is already in place.

As chair of the University Senate and ex officio member of the Board of Governors, I have been asked to sit on a Task Force to work out the parameters of our institutional email, or “organizational junk mail,” as some would call it. This high-level committee spent over half an hour at our meeting on Friday dealing with the complications of what names to use in addressing the mail.

In creating their email accounts, over 1,500 students have chosen to hide their real names. A much larger number have insisted that they have valid reasons not to have their names listed in any directory, whether it be online or in hard copy. And even if we do use their “real names” in sending official mail to them, we were warned that we will have hundreds of complaints about our choice in what that real name should be.

“Get a life!” I said in bureaucratic exasperation. But when I fetched my own mail at the Post Office on the way home, I found a summons to jury duty, which by law I had to sign and return as “Erman Crew.”

“Who do the crowds say that I am?” Louie, many. Mr. Crew, others. Dr. Crew, others (but only during day time hours: Dr. turns into a pumpkin at sunset). His Royal Highness Quean Lutibelle, my innercourt. Husband, Ernest alone. But Erman Crew? Only the feds call me that, and only on solemn occasions, now that my father has been dead for 16 years, the first Erman Crew.

I remember raising chickens as an 11-year-old boy. Fifty years ago, my father took me to open my first bank account, at the Commercial National Bank, the tallest building in Anniston, Ala., all of 10 stories high. We walked up to the marble counter and without even asking me for my opinion, my father handed Miss Margaret (the teller and my Sunday School teacher at Parker Memorial Baptist Church) a slip of paper saying that my account would be in the name of “E. L. Crew, Jr.” Oh, the power of official naming, on June 22nd in the year of our Lord nineteen hundred and forty-eight.

What about you? “Who do the crowds say that you are?” And what is your name? Is it the one given when a priest turned to your parents and said, “Name this child”? Have you added an è sound to it? Has John become Johnny? Joan become Joany? Or have you clipped it? Has Walter become Walt? Has Lewis become Lou? Or have you squeezed a new name into parentheses, Margaret (“Salt”) Smith, M. L. (“Red”) Simpson?

What’s at stake for you in those changes, or in changes that you have successfully resisted? What are the nicknames that have stuck? How did you get them? How have they mellowed with you and you with them? What do the names suggest about “Who the crowds say that you are?”

Names are bit like proofs we get from the photographer: We can’t argue with the claim of each name, or each proof to be us, but we usually have our own clear preference about the name or face we would want to show to the world. And the crowds do not always honor our preference.

Names are also a bit like voice-prints. Do you remember the first time that you heard your own voice on a tape recorder? Psychologists tell us that almost all of us feel, “That is not me at all. That is not the way I sound.” Part of that reaction is that the recorder can never pick up the extra resonance our own head gives to the sound as it leaves our body. But another dynamic is at work as well. The taped version teases many of us to project on it our fears of what we don’t want to sound like. Those of us who are insecure sometimes hear in the tape recording of our voice the person we fear others take us to be, and many of us. We project upon the tape the part of our personhood we are resisting.

I had that reaction for years. Whenever I heard my voice on tape, I would recoil thinking, “That sissy!” All through adolescence and young adulthood I worked hard to keep my pitch low. I also never let my nails grow long, never looked at them this way [fingers pointing away], but only this way [fingers pointing to me]; crossed my legs only at 90 degree angles; never wore green on Thursdays, running in fear away from an identity the neighbors suspected long before I could even name it as my own, much less begin the spiritual process of integrating it.

I want to tell you about Erman Crew, my father. He was a strong man, though never athletic. He loved to read, far more so than most of his better-educated friends did. He constantly gave himself away in service: He chaired the YMCA board, the Community Chest, the Boy Scout Council… He was man of great faith and not afraid to stand against the crowd. He acted out his personal convictions with public integrity. He took a drink, and told the other deacons of Parker Memorial that he did so out of conscience and that they were free to dismiss him as a deacon if that was a problem for them. (Many of them also took a drink but told no one.) They did not dismiss him. In time, as they matured with him, they asked him to teach the men’s Bible class.

Dad strongly disapproved of the way Baptists had of ending a decision with one more ballot, so that all who had voted against the action and lost could now vote for it to make it unanimous. They did this so that they could say more boldly: “The Holy Spirit led us to do it.” Dad never let any vote be unanimous. Even if he was for the action, he would make a point of abstaining, just to keep the vote from being unanimous. Most folks treated this idiosyncrasy as a joke, but he didn’t. He often repeated: “The Holy Spirit is not ours to trick.” My mother and I would often be embarrassed. I can remember saying to her again and again, “Why do I have to have a father who is different from everybody else’s father?” Little did I guess God’s answer to that one!

Dad did not like it when our church acted as if God belonged to us and people just like us. When I was only nine, he took me to the mill village in our town, a squalid place where the dirt poor lived, and had me teach a Bible class to boys my age and younger. Afterwards, I would go play with them and visit in their homes. Later when I read Dickens, I had already been there. Four times a year my father would bring every person from the village and sit them on the front pews where we always sat, so that the members of our church would have the experience of being in God’s house for real, with all of God’s children, and not just shuffle some of them off to a mission. At the time I tended to notice most how the poor smelled.

One of Dad’s favorite stories was about his own father, Louie Crew, president of the bank in Coosa County, one of the scrawniest counties in Alabama. In 1911, when my father was about six, the Ku Klux Klan came to his house, most standing with horse or beside a buggy. The small boy, Erman, stared wide-eyed and fearful in a far corner of the porch at the men, their heads covered with hoods, their torches held high.

“Come on out heah, Louie,” one of their leaders called to my grandfather, who stood eye-to-eye before them, his the only face showing. “No, Johnny. No, Herb. No, cousin Will. No, Mr. Fincher…” How does he know who they are? Erman wondered. It’s a miracle. He knows them even though he can’t see their faces. [Later my Dad noted that as a banker, his father had lent money for every horse and buggy there. The small boy’s wonder derived from his innocence, but not the wonder that endured.]

“No. You men can’t be up to any good if you have to cover your face to do it. I won’t be going with you.”

By the time I got to college, I changed “E. L. Crew, Jr.” to “Louie Crew, Jr.” My grandfather’s first name had been William. He had been long dead, and I so much wished that I had been named for him.

I struggled for years with the image of Erman Crew, whom I loved and respected but could never be like, and I certainly could not be like him if people knew my deep, dark secret. Long before I acknowledged publicly who I am, I came to terms with it privately, even though I did not like the face. I expunged every reference to “Erman” in my name. I wanted to protect him, should I ever be arrested or exposed. Only the feds could keep up with “Erman Louie Crew, Jr.” I could not.

My father and mother found it much easier to deal with my coming out than with my marrying a man who happens to be black. “After all,” my grandmother, Louie’s wife, told them, “He’d already become an Episcopalian. What else did you expect? Of course he had to be queer.” Her father had returned from the Civil War a severe alcoholic and abandoned his family, so my grandmother did not grow up with a sweet disposition.

When I wrote my parents telling them that Ernest and I had married, they wrote a letter saying how glad they were that I had found someone whom I loved. (I was 36 by that time, and I had come out eight years earlier, at 28.) They said they hoped I would understand the hard part, that they did not want to meet him. “We have to live in this community. We are retired and have many friends. We do not want to put them to the test. Most of them would probably pass the test, but we don’t want to find out who would not. We hope you will understand, and we pray that you will love us enough to keep coming to visit, alone.”

I showed the letter to Ernest. He read it, smiled, and put it on the sofa.

“Well, come on,” I said.

“What do you mean?” he asked.

“We’re going to see them. It’s only 250 miles, and we’ll be there in five hours.”

“Didn’t you read the letter?” he asked.

“Yes, but they’re my parents, and I know them, and they’ll love you just as much I do once they get to meet you. After all, you’re just like Mother, and they’ll know that once they’ve been around you…”

“Louie, I am not going,” he said, “but you are.”

“Of course, you’re going, you’re my husband and…”

“I’m not going,” he said. “I respect them. They know who they are. They love you. They’re being very honest with you. They have a right to a peaceful old age. Besides, I did not marry them. I married you. And you could not love me as you do if they had not loved you. So I have the best of their love. And if you do not continue loving them, your ability to love will be diminished. So get in that car and go see them the same way you have done at least once a month since you moved away from home.”

Visit by visit, my mother would grow closer to him as I talked about him. Visit by visit, she would send a bauble back with her gifts of chocolate layer cake. One time, her silver service, which she said she was weary of polishing. Another time, a bracelet she wanted Ernest to have. Another time, her Meito china. The next her Fostoria crystal. Then her wedding ring, so that he might wear it as a pendant.

Dad was more taciturn, but six months into our marriage, he said on one of my visits, “Son, I don’t understand how a child of mine could relate to a n*gra as to an equal. You’ll have to forgive me, for Erman Crew is a child of his generation. But I’ve observed you closely, and you speak of Ernest as an equal. If you were with him because you thought he was inferior, that would be sickness on your part and dangerous for him. The same would be true if you thought you were inferior and not worthy. Clearly that has not happened, and I rejoice for you both.”

“But there is more. I have loved you from before you were born. I remember seeing you for the first time at Garner Hospital. Since you won’t have children, there are things about parenting that you will never know. I remember holding you and looking in your eyes. You are God’s gift to us. I have always loved you. But for most of your growing up, something about you was incomplete. I could not ever put my finger on it. When you became an adult and a teacher, still you were incomplete. It’s only since you joined your life with Ernest’s that you have changed. I can’t understand it. But the incompleteness is gone. I still have my own blinders, and I can’t deny them. I still am not ready to meet Ernest. Please forgive me. But son, you must tell him when you go back home that I have to love him because he had given my boy back to me whole!”

Six years later, Dad called one evening. I answered the phone. “I’d like to speak to my son,” he said. Both sets of parents routinely mistook our answering voice.

“Dad, this is your son,” I teased.

“No, Louie, I’d like to speak to my other son.”

“This one is for you,” I said, handing the phone to Ernest.

My father told Ernest that he and mother had not treated him kindly and asked Ernest for his forgiveness. “Will you come with Louie to visit us?” he asked. They scheduled all of their closest circle of friends to drop by while we were there, and ironically offended many others who thought they too were part of the inner circle and wanted to be there.

Three years later, Mother died in January, and by June, Dad lay near death. I was ending a long visit at the nursing home, and we both knew we would not likely see each other again in this life. “Dad, I know that I am not the son you wanted,” I began. How else could I feel, putting these loving folks through so many more changes than they ever needed or deserved, and right through their retirement. “Dad, I know that I am not the son you wanted, but I want you to know that I love you very, very…”

He was very agitated and extremely weak, down to only 75 pounds. “NNN, NNNN, ” he groaned as he began to pull himself to the railing on the side of his bed to look me eye-to-eye: “Erman Louie Crew, Jr., you are the child that I wanted! You are! You are, dear son, and don’t you ever forget it. I love you very, very much.”

That is just a man. A man I love very much, but a mere mortal. You have been very patient in listening to me natter about him and about his father. But let me tell you about my other Father. “But now that faith has come, we are no longer subject to a disciplinarian, for in Christ Jesus [we] are all Children of God.” God has me standing in this pulpit to tell you personally that You, You, You are the child that God wanted, just as you are! And God our Father loves you very, very much!”

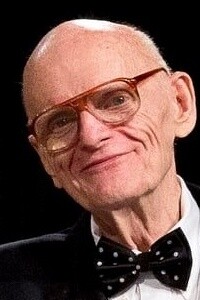

A prolific author and lifelong campaigner for the acceptance and inclusion of LGBT people by Christians and in the mainline church, Dr. Louie Crew Clay founded IntegrityUSA, a gay-acceptance group within the Episcopal Church, while teaching at Fort Valley State University in 1974. He married Ernest Clay in 1974 and then again in 2013, when marriage equality had become the law of the land. Known as Louie Crew for most of his life, he took his partner’s surname in his later years.