Fellowship Congregational Church, Tulsa, Okla.

Reading for the Fourth Sunday in Lent: John 3:14-21

A dear friend and co-worker for human rights, Barbara Santee, has written a play which has just completed its second run at the Heller Theater, and which has been selected to represent the Heller Theater at the Oklahoma Community Theater Festival next weekend in Stillwater. “Trespasses,” the name of the play, is a deeply disturbing portrait of family betrayal and incest. The drama is a gripping story of a young mother’s horrified realization that she has placed her daughter in the care of a child molester. As is the case with most sexual child abuse, the monster in question is a family member, the child’s, apparently, loving uncle. And, as is also frequently the case, the uncle is a leader in the rural community’s church and a man of very strong religious beliefs.

I saw the play Thursday evening, and knowing that it was autobiographical, I was struck with the courage it must have taken to write it. I mentioned this to Barbara following the performance, and she said that it was only when she began to write the play, and thereby bring to the light her pain, and her family’s dark secret, that she began to heal.

Today’s Gospel reading, while a wonderful declaration of the love of God for the world, is also an invitation to let the light of that love shine in our hearts, and expose the darkness therein, so that we too may be healed.

The reading begins with reference to that strange story in the Book of Numbers, read as our Old Testament Lesson. The story takes place in the wilderness, following Israel’s exodus from Egypt. Tired of their complaining, God sends serpents among the people to afflict them. It seems a little harsh of God, but then grumbling can get on anyone’s nerves, even God’s, I suppose. What is interesting is the remedy. After the people repent, Moses goes to God in prayer, and God instructs Moses to make a bronze snake and put it on a pole, so that anyone who looks at it might live.

The notion of focusing on an image of the thing that ails you as a means of healing may contain more truth than is at once apparent What also might be noted, in light of the recent Congressional resolution upholding the display of the Ten Commandments in courthouses, is that this remedy, which, according to the text, God himself gives to Moses, is a direct violation of the Second Commandment, the prohibition against the making of images. The members of Congress who support this resolution, no doubt, are unaware of this discrepancy, but what else might you expect when politicians become theologians!

Of all God’s creatures the snake has the worst reputation. From “poisonous reptile” to “creepy, crawly thing,” the name evokes fear, something to be avoided, or something to be despised, like “the devil”. But there is another side to this creature. The snake in ancient mythology symbolizes healing and transformation. Shedding its skin, the snake was thought to be a creature that was reborn, and so became a symbol of eternal life. In native American spirituality, for example, the snake god, Feathered Serpent, is symbolic of the power that overcomes death, the power of resurrection.

In the ancient middle east, from which our sacred Scriptures derive, the snake was associated with female deities. Sensitive to ambivalence in human intentions, these deities were often depicted as both nurturing and destructive. Inanna, for example, was the Sumerian goddess for both love and war, expressing the human struggle with conflicting wishes and values.

This notion of ambivalence, of the struggle of contrary tendencies in each individual, is pictured by the caduceus, the ancient symbol of the medical profession, a staff entwined by two serpents. The staff is that of Asclepius, the Greek god of healing. The serpents are the opposites that war inside us. As the Rabbis taught, there is a good and evil impulse that contend with each other in every human being. Healing, then, is the positive outcome of this struggle, an overcoming of our ambivalence, an overcoming of our double-mindedness, a bringing of opposite forces together around a common element.

But what is it that is strong enough to bind together the warring opposites inside us? What is it that is great enough to embrace all our pain and all our fears? What is it that can stop the biting serpents? The answer of the text, and the answer of the Gospel, is the love of God, a love greater than which, and stronger than which, nothing can be conceived. For “just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the [Human One] be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.” (NRSV) Imagine that! The cure for snakes is a snake! The cure for human life is the life of one genuinely human! And the cure for death is death! In the lifting up of the Son on the cross God is healing the world. “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish but have everlasting life.” (KJV)

One of the most beloved of New Testament verses, John 3:16, declaring that God loved the world so much as to give his only child, must also have resonated with the ideas of both Jewish and Gentile people of the first century. For it not only draws on the classic Jewish elaboration of the theme of the beloved son in Genesis, but it also recalls the Canaanite story of the deity who sacrifices his only child to avert social calamity. (Levenson, The Death and Resurrection of the Beloved Son) God’s giving up of his own child for the sake of the world is a powerful image, but it is an image that does not work for everyone. People who work in the area of domestic violence raise the question whether the death of a child to redeem the world does not perpetuate notions of victimhood and violence in human relationships, a critique that is not absent in Barbara Santee’s play that I referred to a moment ago.

Let it be said, then, that what is at stake in this famous verse of Scripture is not the image itself, but what the image seeks to convey. And what the image seeks to convey is the revelation of the love of God, a love so great that it breaks the divine heart. It is not that the Father sacrifices his Son. That’s not the point of the image. The point of the image is the costliness of the divine love, the lengths to which divinity goes to reach us and heal us. The revelation to which the cross points is a transaction within the heart of God. For only something that costly, and that astounding, can save us.

There is another misunderstanding that is possible with this beloved verse. “God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish but have everlasting life.” The minor premise is the requirement to believe, the implication being that those who do not believe, as is stated a verse later, are condemned. If what is meant here by “believe” is becoming a Christian, then the next question has to be, What kind of Christian? Because there are different kinds of Christianity. And two thousand years of church history strongly suggest that a lot that has gone on under the rubric of “Christian” has little to do with Jesus! Certainly the writer of this wonderful verse of Scripture has something else in mind than predicating salvation on religious adherence.

What the writer of this verse of Scripture has in mind, I believe, is not advocacy of another religion, even the Christian religion; but what the writer has in mind is revelation. What is revealed on the cross is the divine heart. What is revealed on the cross is a love that can heal us. What is required is to see it, whatever one’s religion. And that is what it means to believe. To believe is to see. This is how the verb “to believe” is used throughout John’s Gospel. Believing means seeing. Those who see what is going on in the event of the cross enter into a dimension of existence called “eternal life”, the meaning of which is not duration in time, but a quality of life over which death is no longer a threat. Neither time nor death qualify or modify the kind of life into which one enters when one sees and is embraced by the divine love, revealed on the cross.

Francis Bernadone wandered into a church in Assisi one day and stood under the crucifix over the high altar. He looked on the dead body, impaled on the cross before him — stark, simple, and demanding — and he saw something. He saw the power in such love. And seeing such love, something began to work inside him. It set him on a journey, the journey toward becoming St. Francis of Assisi.

There is a catch in all this. There always is. Things are never quite as simple as we would like them to be. And the catch is this: What happens to those who don’t see? What happens to those who don’t “get it”? The writer of these verses struggles with this issue. The writer is so caught up in the revelation of the divine love, that he, or she, cannot imagine anyone not being swept up as well. But the truth is that not everyone does see. Or is it, that they don’t want to see? The writer expresses it this way: “God did not send the Son into the world to condemn the world, but in order that the world might be saved. . . This is the judgment, that the light has come, and people loved the darkness rather than the light.”

The truth being expressed here is that the coming of light is a mixed blessing. While light may illumine our way, reveal to us the divine love, light also may show us what we would prefer not to see, what we would prefer to remain hidden. There is seldom illumination without shadows. Turning on a light in a room full of roaches would not be an occasion of joy for the roaches! (Craddock, John, p. 31) Some things thrive in darkness and cannot stand the light. So does light bring both blessing and judgment. What may be a stepping stone for some is a stumbling block for others.

I think of our study last year of homosexuality and Christian faith, how for many that study meant enlightenment, but not for all, and how painful it was for me to recognize that what for some was light, for others, darkness. How different are our perceptions.

What then shall we say? This is the Apostle Paul’s question, reflecting on the divine love in chapter eight of his Epistle to the Romans. And, while Paul’s words were written first, they comprise a wonderful commentary on John’s declaration. What shall we say? We shall say this: “If God is for us, who can possibly be against us? He who did not withhold his own Son, but gave him up for us all, will he not also give us every thing else? . . . For I am convinced that neither death nor life. . . nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God [which we have come to see] in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

Here, dear friends, is a love big enough to embrace us all, regardless of our varied perceptions of truth. And here is a love powerful enough to absorb our pain, even the pain of Anita, of Rosemarie and Butch. There is a balm in Gilead. But this declaration of such a wondrous love is at the same time an invitation to pray with the Psalmist, “Search me and know me, O God, and see if there be any wicked way in me.” Let the light of such wondrous love bring to the surface and deal with the darkness, not in our neighbor’s soul, which judgment we can safely leave with God, but is there any darkness in our own, that we too may be healed.

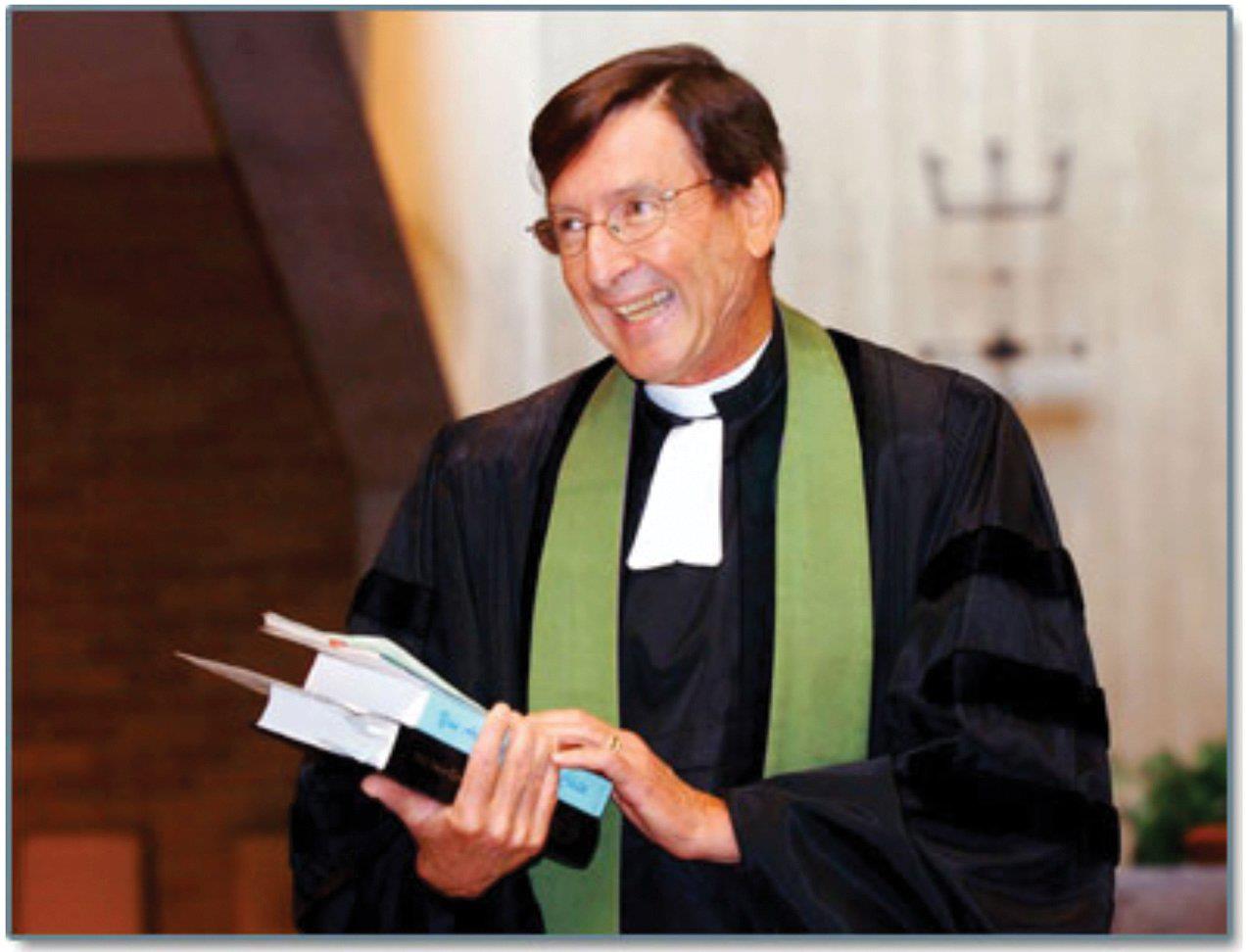

A leader in the Tulsa, Okla., interfaith community for more than three decades, Rev. Russell L. Bennett served as minister of Fellowship Congregational Church, the first mainline church in northeastern Oklahoma to openly welcome gay men and lesbians, for 36 years until his retirement in 2004. He helped found the Tulsa Interfaith Alliance in the 1980s and served as its president until 2006. A native of Los Angeles, he was raised in the Evangelical and Reformed Church, which merged in 1957 with the Congregational Christian Churches to form the United Church of Christ. He earned a master’s degree from Harvard Divinity School and a doctorate from McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago. His book You Are God’s Beloved Child contains writings from his years of ministry.