Women’s History Month doesn’t do enough to lift up black lesbians.

Fifty years ago in Boston, several lesbian and feminist women of African descent founded the Combahee River Collective. As a sisterhood, they understood that their acts of protest were shouldered by and because of their ancestors — known and unknown — who came before them. Its name honors the military action of abolitionist Harriet Tubman — known as the 1863 Combahee River Raid — that freed more than 750 enslaved people.

The CRC’s founders and frequent participants were an A-list of Black feminism’s foremothers: Cheryl Clarke, Demita Frazier, Gloria Akasha Hull, Audre Lorde, Chirlane McCray, Margo Okazawa-Rey, and twins Barbara and Beverly Smith. It was formed to respond to the Black Nationalist and misogynistic politics of the Black Power Movement and the exclusionary practices of white feminism.

The social upheaval of the 1960s and 70s revealed a confluence of political struggles — the Vietnam War, Black Civil Rights, Black Power, Women’s Rights, and LGBTQ+ rights movements — that informed and ignited Second Wave Feminism. In Boston, the busing crisis and the Roxbury murders of 11 black women in 1979 added to the explosive tenor. The surge of activism and organizing was epic, and the CRC was in the mix.

Black feminists

The National Black Feminist Organization (1973–76) was formed in New York City at a time when the single-issue agendas of Black men and white women ignored the oppressions of racism and sexism that Black women confronted. In the 1970s, NBFO was one of the earliest and most influential Black feminist organizations in Second Wave Feminism, with 10 chapters nationwide. The Boston Chapter of NBFO broke away, with Barbara Smith and Demita Frazier helping to form the CRC.

The breakaway from NBFO happened for many reasons, one of them being that CRC was anti-capitalist.

“We believed socialist theory was important as we considered the material situations of Black women under capitalism. That did not appear to be a conversation taking place in the NBFO,” Frazier told The Nation in 2021.

For poor Black and LBTQ women, NBFO was too myopic in its scope and in advocating for them because of its “bourgeois-feminist stance.” Because CRC was radical, grassroots and inclusive in their organizing efforts across diverse racial, class and identity groups, it felt that by explicitly challenging homophobia, the NBFO in contrast would not do enough to address the specific needs of Black lesbians in organizing as Black feminists.

The Statement of the Combahee River Collective

In explaining Black women’s lives as interlocking oppressions (laying the groundwork for the theory and practice of intersectionality), the Combahee River Collective Statement is one of the most referenced manifestos across various identity groups and movements.

The most famous and powerful line in the Statement captures CRC’s core belief:

If Black women were free, it would mean that everyone else would have to be free since our freedom would necessitate the destruction of all the systems of oppression.

Simply put, it means all systems of oppression impact Black women. If Black women’s interlocking systems of oppression were eradicated, then all other marginalized groups would be free, too.

In depicting the struggles of Black women, the term “identity politics” was coined, often maligned by the Left and the Right, and used to justify separatism. But separatism is antithetical to CRC’s core actions of coalition-building.

However, “identity politics” means that because Black women’s lived experiences in a capitalist hetero-patriarchal society choke our quality of life, we have the right to determine our political agenda.

The Statement’s principal writers were Demita Frazier and Barbara and Beverly Smith. Asked in a 2014 interview whether the Statement’s writers knew at the time what a seminal document they were writing, Frazier replied:

We wrote it as a collective. We crafted the Statement at a time it was ready to be heard. The content and the fullness of it came from our conscious-raising groups and testifying with one another. Although we were young and evolving, we wanted to ensure an intergenerational connection to Black and women of color feminism.

And still, we rise!

To kick off Black History Month last year, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis rolled out his list of banned Black books. I told Smith I was amused to see the CRC Statement not banned from Florida’s AP African American Studies curriculum.

“I don’t know why the Combahee remains, but it’s a primary document,” Smith said, laughing. “It’s not an individual saying this is what I think Black feminism is as an individual. It’s a political manifesto.”

The Statement has informed the activist and political framework for Black feminist organizing in Puerto Rico and the Black Lives Matter Movement. It’s referenced in academic, political, and grassroots discourses on reparations, mass incarceration, homelessness, and now in the #MeToo movement. The Statement is frequented in African-American Studies, feminist studies, and LGBTQ+ studies — all subjects that DeSantis has loudly criticized as part of “woke” culture.

The CRC was only active from 1974 to 1980, but its impact is alive today.

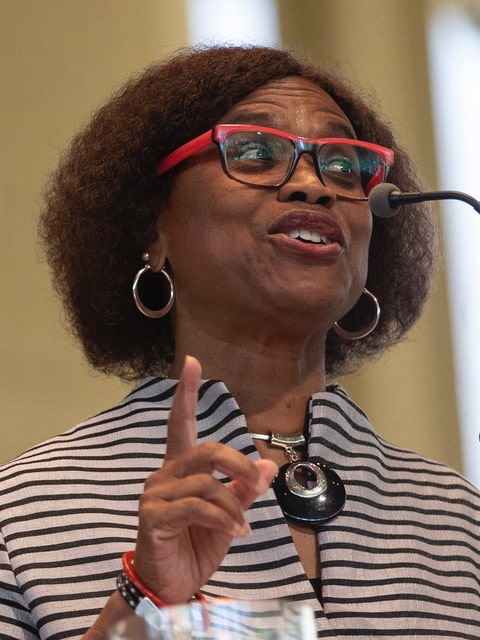

Public theologian, syndicated columnist and radio host Rev. Irene Monroe is a founder and member emeritus of several national LBGTQ+ black and religious organizations and served as the National Religious Coordinator of the African American Roundtable at the Center for LGBTQ and Religion Studies in Religion at Pacific School of Religion. A graduate of Wellesley College and Union Theological Seminary, she served as a pastor in New Jersey before studying for her doctorate as a Ford Fellow at Harvard Divinity School and serving as the head teaching fellow of the Rev. Peter Gomes at Memorial Church. She has taught at Harvard, Andover Newton Theological Seminary, Episcopal Divinity School and the University of New Hampshire. Her papers are at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College’s Research Library on the History of Women in America.