Civil rights activist Rev. Jesse Jackson, who died on February 17, was a protégé of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and among the last remaining icons of the modern Civil Rights Movement. Known for his fiery oratory, he was once nicknamed “The Country Preacher,” a moniker that became the title of a spoken-word album and reflected both his humble roots and his lifelong commitment to advocating for the disenfranchised.

His famous speech, “I Am Somebody” — also the title of a 1971 spoken-word album — resonated deeply at the time with me as an orphan and ward of New York City. In 1984 and again in 1988, I voted for Jackson because he was the only presidential candidate whose campaign openly welcomed people like me: an African American lesbian.

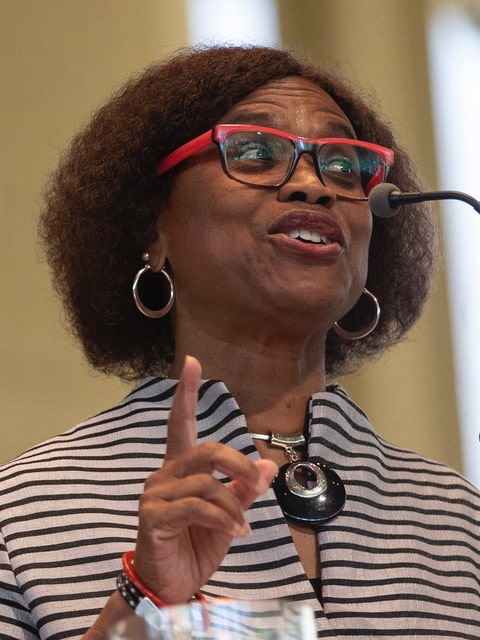

In 2018, I met Jesse Jackson at the Chautauqua Institution, where I was the guest preacher for the week. I thanked him for his decades of public service.

The LGBTQ+ inclusive Rainbow Coalition

“Rev. Jesse Jackson believed political power was built through coalitions. In 1983, he came to Boston’s South End [Concord Baptist Church] to support Mel King’s mayoral campaign, a multiracial progressive movement many thought couldn’t win,” said Sue O’Connell, editor and co-publisher of Bay Windows, in an interview on Boston’s NBC10 the day Jackson died. “Here’s something people don’t realize — it was Mel King who coined the term ‘Rainbow Coalition.’ Jackson saw what King was building in Boston and took that concept national. So Boston plays a major role in Jackson’s legacy.”

Jackson’s deep ties to Boston began with King. Called the godfather of the Rainbow Coalition, Mel King (1928–2023) was a revered community organizer, educator and towering figure in Boston politics.

Jackson adapted King’s coalition model for his own presidential campaigns in 1984 and 1988. Reflecting on King’s impact, Jackson recalled in Progressive City: Radical Alternatives (1999): “I first laid eyes on Mel at a rally against racism on the Boston Common in 1974… I was electrified.” Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition brought national visibility to constituencies many politicians regarded as liabilities—among them feminists and LGBTQ+ Americans.

King’s coalition model disrupted Boston’s historically fragmented and racially polarized political establishment.

Although he lost his historic 1983 mayoral race, his grassroots strategy — uniting Black, Latino, Asian and progressive white voters — proved to be successful for future candidates.

It helped pave the political paths for President Barack Obama and U.S. Rep. Ayanna Pressley. Former Democratic presidential nominee Michael Dukakis, reflecting on Jackson’s death, acknowledged in an interview with local TV station WCVB that Jackson’s 1988 “Keep Hope Alive” campaign was a key precursor to Obama’s 2008 “Yes We Can” victory.

A courageous voice in the early days of HIV/AIDS

During the AIDS epidemic, the Black LGBTQ+ community often found neither refuge nor welcome in the church. Many persistent social, political, and economic factors fueled the high rates of HIV/AIDS in African American communities — racism, poverty, healthcare disparities and violence, to name a few. Yet the most damaging factors were the homophobia within the Black Church and its entrenched politics of silence.

“I grew up in the Black Church,” Dr. David Satcher, former Surgeon General and Assistant Secretary for Health, told The New York Times in 1998. “I think the church has problems with the lifestyle of homosexuality. A real problem has been getting ministers who are even willing to talk about it from their pulpits.”

Jackson was among the first Black ministers and political leaders to promote AIDS education and prevention. He worked to destigmatize the virus by becoming the first Black clergy member to be publicly tested.

He also mobilized fellow clergy to action, reframing HIV/AIDS as a public health crisis rather than a moral failing tied to LGBTQ+ identity.

In 2002, through the Rainbow PUSH Coalition, Jackson launched the “One Million Tests” initiative to encourage HIV testing in African American communities and to pressure pharmaceutical companies to lower the cost of antiretroviral drugs.

Jackson didn’t stop at challenging Black ministers; he also called out President Ronald Reagan. In a speech delivered at Northeastern University in May 1987, Jackson expressed outrage over Reagan’s prolonged silence. When the president finally acknowledged the epidemic, Reagan belatedly labeled AIDS “public health enemy number one” — without recognizing how his own inaction had contributed to its devastating spread.

Fearless champion of marriage equality

“Marriage is based on love and commitment — not sexual orientation. I support the right of any person to marry the person of their choosing,” Jackson declared at a rally outside the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in San Francisco in December 2010.

Jackson was a full-throated supporter of LGBTQ+ rights. He opposed California’s Proposition 8, which defined marriage only between a man and woman, rejected the idea that marriage equality should be decided state by state, and stated publicly that he would officiate same-sex weddings.

However, like many Black Americans, he strongly objected to comparing the LGBTQ+ rights movement to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

That tension was thoughtfully addressed during a June 12th Capitol Hill ceremony marking the 40th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision striking down anti-miscegenation laws and sponsored by a coalition of mainline and LGBTQ+ civil rights organizations nationwide.

In conjunction with the event, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund released a historic statement clarifying why the fight for marriage equality is indeed a civil rights struggle:

It is undeniable that the experience of African Americans differs in many important ways from that of gay men and lesbians; among other things, the legacy of slavery and segregation is profound. But differences in historical experiences should not preclude the application of constitutional provisions to gay men and lesbians who are denied the right to marry the person of their choice.

Rest in power, Reverend

Jackson advocated for the LGBTQ+ community — especially Black LGBTQ+ people — at a time when we had no one. He offered hope when family, church, and society turned their backs on us. In this dark political moment, when hard-won civil rights are being targeted and rolled back, he leaves us with the enduring charge from his 1988 speech: “Keep Hope Alive!”

Public theologian, syndicated columnist and radio host Rev. Irene Monroe is a founder and member emeritus of several national LBGTQ+ black and religious organizations and served as the National Religious Coordinator of the African American Roundtable at the Center for LGBTQ and Religion Studies in Religion at Pacific School of Religion. A graduate of Wellesley College and Union Theological Seminary, she served as a pastor in New Jersey before studying for her doctorate as a Ford Fellow at Harvard Divinity School and serving as the head teaching fellow of the Rev. Peter Gomes at Memorial Church. She has taught at Harvard, Andover Newton Theological Seminary, Episcopal Divinity School and the University of New Hampshire. Her papers are at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College’s Research Library on the History of Women in America.