The long-awaited justice for R. Kelly’s survivors finally came last month when a New York federal jury found him guilty of racketeering and sex trafficking.

For nearly 30 years, underage black girls and their families have tried to bring Kelly to justice. Now the question being asked is: What took so long?

“The entertainer had an expansive network of enablers around him, federal prosecutors said, from his closest confidantes and employees to many in the music industry who knew of the concerns about his behavior but did not intervene,” wrote Troy Closson, a reporter for The New York Times covering law enforcement and criminal justice.

Several institutions failed these black girls, though, including the judiciary, law enforcement, and the black community and church.

In 2002, on the same day after posting a $750,000 bond on child pornography charges, Kelly left the court to attend a children’s graduation ceremony at Salem Christian Academy in Chicago.

One would think Kelly’s sing-along with the kindergartners would land him back in jail. But accompanying Kelly from the courthouse to the graduation was the renowned Rev. James Meeks, Kelly’s spiritual adviser and senior pastor at the Salem Baptist Church.

In 2019, after the airing of Lifetime’s docu-series “Surviving R. Kelly,” which sparked a national outcry, the seven-time gospel Stellar Award winner Bishop Marvin Sapp was called on the carpet for his association with R. Kelly.

In 2017, Sapp released a song titled “Listen,” featuring Kelly. In an interview on the black gospel radio show “Get Up!” in 2019, Sapp first defended his position, stating they recorded the tune before the controversy.

Of course, you must wonder what world Sapp had been orbiting in, since there had been controversy around Kelly for decades.

When Black Twitter pounced on him for his lame excuse, Sapp said prayer was part of his reasons for releasing the song. “After praying about it — in studying scripture — one of the things that I think that all of us in the body of Christ need to notice is that the message has always been bigger than the messenger,” Sapp said. “I think many of us miss that. When you study scripture, you will notice that when God decided to do something great, God chose a flawed individual.”

Black women have decried how black pastors have used self-serving theological reasoning in supporting Kelly and the deleterious effects it has had on them, reporting sexual abuse and rape, especially by their male parishioners, deacons and pastors.

Studies have revealed that black girls, women and nonbinary individuals confront higher domestic violence and rape incidences. Nearly 60 percent of black girls are sexually abused before 18, and black women are killed at a higher rate than other women.

Brittany Packnett Cunningham tweeted to Sapp:

.@marvinsapp, there are women being abused in your congregation, and pastors who take their example from you.

Everyday you stay silent and support #RKelly, you send the message that abuse of black women is permissible-especially in the church, the place we should be safest.

According to Rolling Stone, R. Kelly album sales have been up by 517 percent since his guilty verdict, which is no surprise — it’s a trend that follows controversy. But it begs the question: Are Kelly’s R&B and black gospel followers the ones buying his music on the down-low since it’s now taboo to do so?

In a Religion News Service essay, Cheryl Townsend Gilkes has posed her question about R. Kelly’s music to the church, “Will the Black church continue to sing ‘I Believe I Can Fly’?”

Gilkes, a native Cantabrigian, professor at Colby College and assistant pastor for special projects at Union Baptist Church in Cambridge, notes that “from its beginnings, gospel music has had a strained relationship with commercial interests and secular artists.”

“I Believe I Can Fly” first appeared on the soundtrack for the 1996 film “Space Jam,” and then in 1998 on Kelly’s album R. At the 1998 Grammys that year, Kelly performed the song backed by a gospel choir. Gilkes reminds readers that “I Believe I Can Fly” resonates in the black community because the “flight” trope has been a core theme in our culture since slavery to the present day.

The trope is expressed in black art, literature, and black liberation theology as a form of resistance and inspiration. And it’s one of the reasons the song is sung ad nauseam at funerals, weddings, and graduations and in churches.

Gilkes hopes the black church won’t sing “I Believe I Can Fly.” I want the church to do more: Stop being on the down-low about sexuality and sexual abuse and develop an embodied theology. As a child of sexual abuse, R. Kelly needed help. The girls Kelly held captive and abused needed rescue from him. The black church missed the opportunity to help both.

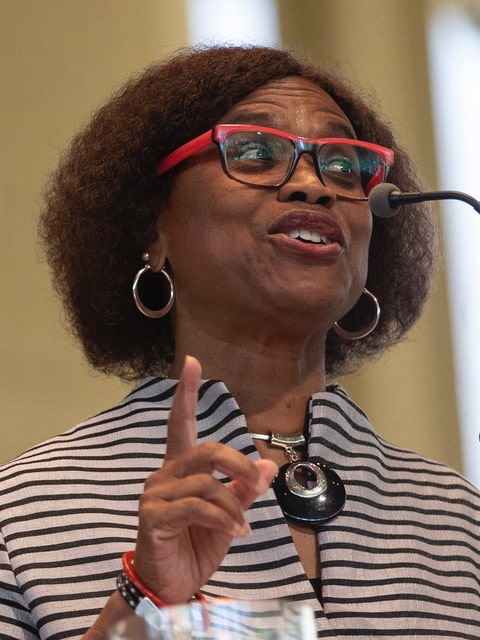

Public theologian, syndicated columnist and radio host Rev. Irene Monroe is a founder and member emeritus of several national LBGTQ+ black and religious organizations and served as the National Religious Coordinator of the African American Roundtable at the Center for LGBTQ and Religion Studies in Religion at Pacific School of Religion. A graduate of Wellesley College and Union Theological Seminary, she served as a pastor in New Jersey before studying for her doctorate as a Ford Fellow at Harvard Divinity School and serving as the head teaching fellow of the Rev. Peter Gomes at Memorial Church. She has taught at Harvard, Andover Newton Theological Seminary, Episcopal Divinity School and the University of New Hampshire. Her papers are at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College’s Research Library on the History of Women in America.