This past Valentine’s Day, I pay homage to W. E. B. Du Bois’s 1924 novel Dark Princess because it highlights the least talked-about subject then and now: Black love.

Two activities converged for me during COVID-19: When not officiating funerals, I read romance novels and took long walks along the Charles River, thinking about W. E. B. Du Bois as a romantic.

During my morning constitutional, I intentionally passed 20 Flagg Street, where sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois, the first African American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard University, resided from 1890 to 1893 while a doctoral student because of the University’s segregated housing policy prohibiting Blacks in the dorms. Since 1994, thanks to then-Mayor Kenneth Reeves (the first gay and Black mayor of Cambridge), the house is part of the Cambridge African American History Trail, and the Cambridge Historical Commission placed a marker in the front yard to commemorate Du Bois’s life.

During COVID, I happened upon a romantic novel by Du Bois titled Dark Princess, A Romance Novel. I was in disbelief. Du Bois said that of his body of work, Dark Princess, A Romance Novel was his favorite. Because the book was on sale on Amazon as a Kindle ebook for $2.99, I thought to myself, what did I have to lose? Moreover, the thought of Du Bois having written a romance novel didn’t fit the image of the man I learned about in college.

Born three years after the American Civil War in 1868 and died one day before the historic March on Washington in August 1963, Du Bois is known as one of last century’s preeminent scholars on African American life. Known as Willie to family and friends, Du Bois spent his formative years in the Berkshires community of Great Barrington, Mass., approximately a 2-1/2-hour drive from Boston. I wonder if it was during his time in Great Barrington, with less than 30 African American families, that the seed of his concept of “double consciousness” began to take root when he depicted it in his 1903 seminal and autoethnographic text The Souls of Black Folks.

Dark Princess was written in 1924 during the Harlem Renaissance. This cultural and artistic movement promoted Black America’s causes, hopes, dreams, and genius through its Black intellectuals, musicians, writers, poets, and artists such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston and James Weldon Johnson.

Dark Princess was Du Bois’s effort to showcase Black love while illustrating his concept of the “problem of the color line” at home and abroad and the need for solidarity across races. While the book shows that Black and Brown lives globally are constantly challenged, it also highlights that we must find time for joy, love, and celebration as a radical act of liberation.

The protagonist, Matthew Townes, an aspiring student of obstetrics, is told that because he’s African American, he’ll not be permitted to treat white patients, bringing the opportunity to complete his studies to a halt. With shattered dreams, Townes goes to Berlin, where he meets Kautilya, a Southeast Asian princess who’s the daughter of Maharaja of Bvodfur. While Kautilya educates Townes about the racial struggles all people of color confront globally against white supremacy, a romance blooms between them, and they marry.

African American life in the U.S. is primarily depicted as a struggle devoid of romantic love rather than a radical act of living, liberation and loving families. Under the tyranny of colonization, slavery, Jim Crow and simple everyday life, how do we have time for romance? Or a softer racial spin on the subject: I’ve been asked whether, as a people who are so fixated on freedom, we have the capacity for romantic love? Also, bombarded by the iconography of negative images and racial tropes on multimedia platforms of Black women as emasculating females, mammies, welfare mothers — and Black males as “super-predators,” pimps, and roving phalluses — the perception is that Black people don’t engage in romance; we have sex. We make babies.

Du Bois concludes the novel with the birth of Townes’s son, showing that love exists in Black and interracial families — both taboo topics until Mildred Loving (Loving v. Virginia, 1967), who’s often overlooked in the pantheon of African-American trailblazers who are celebrated in February during Black History Month. Loving gained notoriety when the U.S. Supreme Court decided the landmark case in her favor that anti-miscegenation laws are unconstitutional. Her crime was this country’s racial and gender obsession: Interracial marriage. Married to a white man, Loving and her husband were indicted by a Virginia grand jury in October 1958 for violating the state’s Racial Integrity Act — which was passed in 1924, the same year Du Bois’s novel appeared.

Loving understood the interconnection of struggles and supported the same-sex marriage fight.

Today, we are free to marry who we want. Black LGBTQ+ couples can give thanks to Du Bois, who led the way with his novel, and to Loving, who challenged the law. Both illustrated what Black love and families really look like.

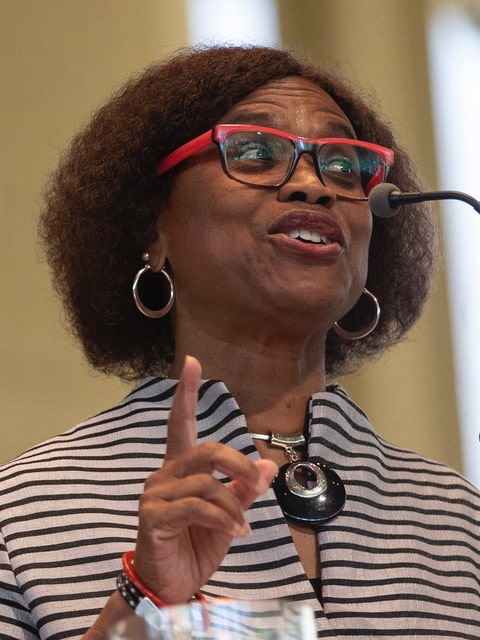

Public theologian, syndicated columnist and radio host Rev. Irene Monroe is a founder and member emeritus of several national LBGTQ+ black and religious organizations and served as the National Religious Coordinator of the African American Roundtable at the Center for LGBTQ and Religion Studies in Religion at Pacific School of Religion. A graduate of Wellesley College and Union Theological Seminary, she served as a pastor in New Jersey before studying for her doctorate as a Ford Fellow at Harvard Divinity School and serving as the head teaching fellow of the Rev. Peter Gomes at Memorial Church. She has taught at Harvard, Andover Newton Theological Seminary, Episcopal Divinity School and the University of New Hampshire. Her papers are at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College’s Research Library on the History of Women in America.