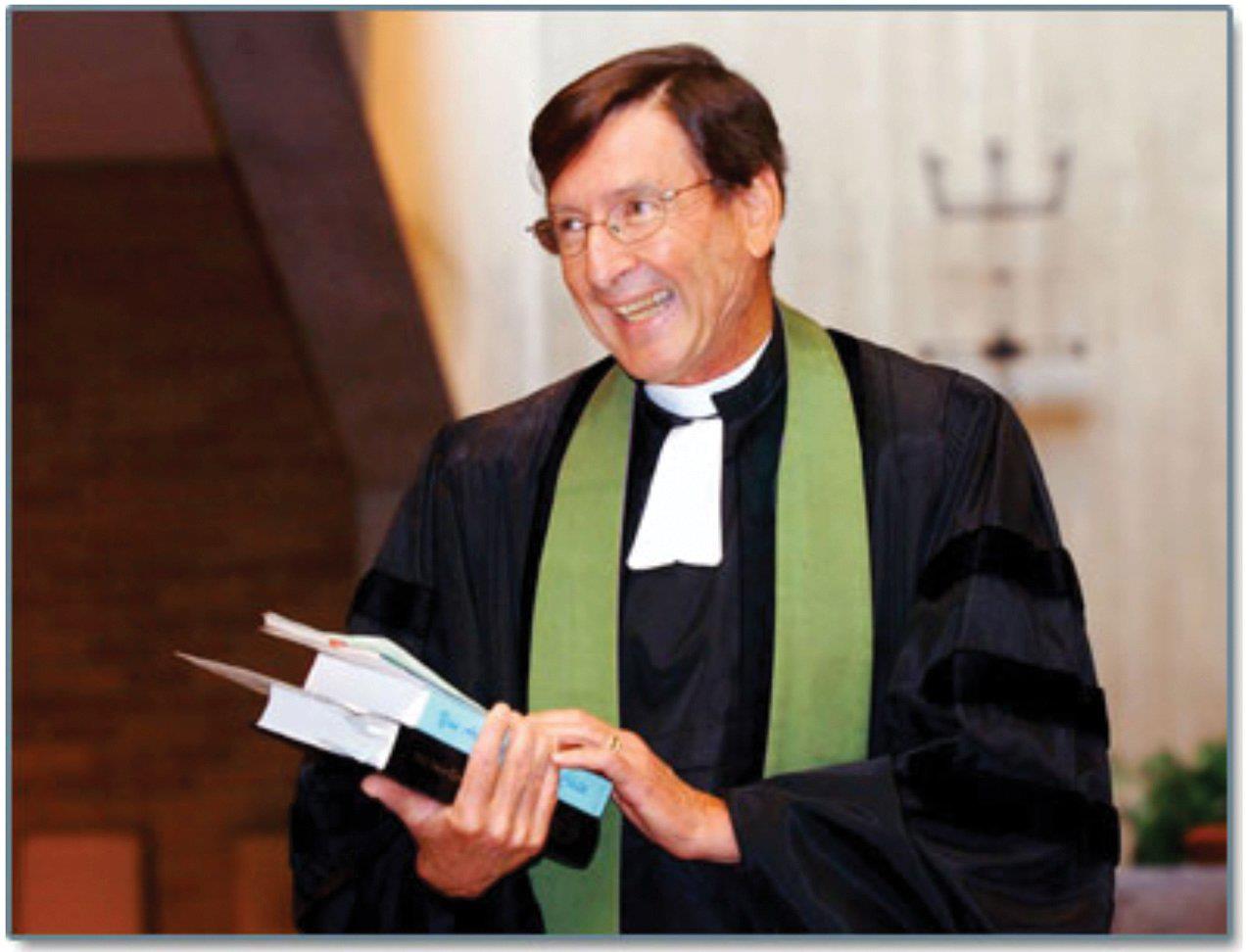

Fellowship Congregational Church, Tulsa, Okla.

Reading for the Fifth Sunday after Epiphany: Luke 5:1-11

You can always tell what is going on in the United States by what people are willing to spend their money on. Books about religion or the sacred are currently better than a three billion dollar annual business. As the religion editor for Publishers Weekly, Phyllis Tickle ought to know. “Religion, the Spiritual, and the Sacred are big business in America,” she writes in the preface to her recent book Re-discovering the Sacred, Spirituality in America.

There is a great hunger for God is the theme of Tickle’s book. She believes that discoveries and circumstances over the past hundred years, circumstances and discoveries that she documents, have triggered this current interest in the sacred. These wrenching events have made us feel cut loose from everything we previously felt sure of. “The last time something similar happened,” she writes, “history labeled the whole thing the Renaissance, or in plain English, the ‘Rebirth.'” We may be, she suggests, on the brink of some kind of re-birth.

Today’s Gospel is a story about how a number of first century Jews in meeting Jesus encountered the sacred. Standing on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, people are pressing on Jesus to hear from him the Word of God. Jesus gets into one of the boats anchored near by, presumably so that all can better see and hear him. When he’s finished, he tells the owner, Simon, later to be called Peter, to put out into the deep water for a catch. Simon, understandably feels he knows more about fishing than this amateur. He’s also exhausted from having fished all night and caught nothing. Nevertheless, for some inexplicable reason he does what he’s told. And what do you think happens? It’s the biggest catch in history! When Simon Peter sees it, he falls down at Jesus’ knees — no easy thing to do in a little boat! “Go away from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man!” he says. Jesus says not to be afraid. He’s got bigger plans for Peter and the others. And when they got back to shore, they left everything, we are told, left it right there on the beach, and followed him.

The story sounds like a fish story, doesn’t it? “You think you had a big catch, well let me tell you about the time we fished all night, and then in the morning this stranger. . .” It also sounds a lot like a story John tells, although in John’s Gospel it comes at the end. In John’s Gospel it is an Easter story, a story of an appearance of Jesus as the Resurrected Christ. What this suggests to me is that Luke has drawn on a remembrance of a resurrection appearance and projected it back to the beginning of Jesus’ ministry. The question is, Why? I believe it is to answer something very puzzling about the call stories in the other Gospels. The tradition was well established by the time Luke wrote that the first disciples of Jesus left everything to follow him. The question is, Why? Why would people leave everything to follow this Jesus? Luke’s answer, and this makes sense to me, is that in meeting Jesus, they encountered the divine. Nothing is the same, “There is a new creation,” as the Apostle Paul expresses it, after one has experienced God. And that is what it meant to meet Jesus. It was to encounter God.

Peter’s reaction to the big catch says it all. He falls down before Jesus and says, “Go away from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man!” Where have you heard that before? That was also Isaiah’s reaction to his experience of the holy, as told in the first reading. “In the year that King Uzziah died,” Isaiah writes, “I saw the Lord.” He describes this awesome experience, to which he responds with the words, “Woe is me! I am lost. . .” Both Peter and Isaiah’s reaction to their experience of the holy is classic. It is what you feel when you experience the sacred.

Now when Peter says, “Get away from me, Lord, for I am a sinful man,” he’s not referring to some moral fault. He’s not saying, “O what a bad person I am.” No, rather like Isaiah, he is speaking of the sense of distance from the divine, the separation from God, that he is experiencing. When you are in the presence of truth, you become aware of how untruthful your life is. When you are in the presence of what is truly real, you become aware of how superficial your life is. Consciousness of the sacred relativizes all else. The things we quarrel about, the things we spend our life trying to get, the things we think are so almighty important, are seen in the presence of the sacred for what they really are: Nothing at all, a striving after the wind! Only God is real. Anything that is real, anything that has any substance to it, is an expression of God. To have God is to have everything. Not to have God is to have nothing.

So, Luke is saying, it is no big deal to give up everything and follow Jesus, because Jesus puts one in touch with God. Notice that Jesus does not tell them to give up everything. That is the difference between Jesus and a cult figure. All Luke is saying is that Jesus puts one in touch with the divine. On the basis of that experience each person determines what is appropriate for him or her. The point is that the quest for the divine determines all else. This is the one thing for which you will abandon everything, because God is everything. To know God, to know what is real, to know the truth, is to be set free.

Note that the story does not tell us that Jesus was divine. Jesus was not a god. It is precisely because Jesus was human, like you and I are human, that the story works. What the story tells us is that in meeting Jesus, in hearing Jesus, in following Jesus, in doing what he tells you, in putting out into the deep, you may experience the divine, as he experienced the divine.

I think the distinction that Marcus Borg makes is helpful. In his earlier book, Meeting Jesus Again for the First Time, and in the one the Book Study group is currently reviewing, The God We Never Knew, Borg distinguishes between “the pre-Easter Jesus” and “the post-Easter” Jesus. The pre-Easter Jesus is the Jesus of history. He was a first century Jew, a remarkable teacher and social prophet. What most clearly distinguishes him, Borg writes, is that he was a “spirit person,” what has traditionally been called a holy man, one who was aware of the reality of God and could communicate that reality.

The post-Easter Jesus is something else. The post-Easter Jesus is the Jesus of Christian tradition and experience. He is the one whom his disciples, after his death, experienced as a living reality. No longer limited to his physical body, no longer confined to space and time, he could be experienced anywhere, anytime. Increasingly he was spoken of as having the very qualities of God. Prayers were addressed to him as God. It is this figure, the post-Easter Jesus, the Christ, the risen Lord, that we meet in the worship and devotion of the Christian community.

I find this a helpful distinction. It is helpful, because it clarifies what was going on when Jesus called people to follow him. As one who was aware of God, who was conscious of the sacred, he called others to be also. As he was in contact with the divine, so he helped others to be. That is why they gathered around him to hear him speak the word of God, that is why at his word they put out into the deep, even though they had fished all night, and that is why they gladly followed him. He satisfied the deepest hunger of their hearts. That hunger and thirst is for God.

The message of the Christian community is that while the pre-Easter Jesus was executed, he is not lost to us. As the Christ of faith, as the post-Easter Jesus, the Jesus who lives in the consciousness of the Christian community, he continues to call people to follow him, and he continues to put people in touch with the realm of the divine. He continues to satisfy the hunger and thirst of the human soul. He continues to be a reliable guide for the spiritual quest.

Everyone of us here this morning has met Jesus, whether in Sunday School or Church, or simply as a significant figure of western culture. It is very difficult not to have heard something about him, given his place in world history. So we carry with us certain ideas or beliefs about him, or images of him. Some of these may need to be discarded, some revised. The invitation of this morning’s text is to meet him again as if for the first time. The invitation of this wonderful story is to experience Jesus as those first disciples did, as one who opened up a new world for them, who called them out into deep water, who put them in touch with the sacred, who transformed their lives, who gave them a new vocation, a new sense of purpose and reason for being.

“Do not be afraid,” he says. Trust him. Meeting Jesus is the beginning of a wonderful and life changing journey. Bon voyage!

A leader in the Tulsa, Okla., interfaith community for more than three decades, Rev. Russell L. Bennett served as minister of Fellowship Congregational Church, the first mainline church in northeastern Oklahoma to openly welcome gay men and lesbians, for 36 years until his retirement in 2004. He helped found the Tulsa Interfaith Alliance in the 1980s and served as its president until 2006. A native of Los Angeles, he was raised in the Evangelical and Reformed Church, which merged in 1957 with the Congregational Christian Churches to form the United Church of Christ. He earned a master’s degree from Harvard Divinity School and a doctorate from McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago. His book You Are God’s Beloved Child contains writings from his years of ministry.