Fellowship Congregational Church, Tulsa, Okla.

Reading for Transfiguration Sunday (Last Sunday after Epiphany): Luke 9:28-36

Early 20th century English writer G. K. Chesterton once defined philosophy as “thinking that had been thought out.” We are influenced, Chesterton went on to say, either by thought that has been thought out or thought that has not been thought out, and which it is makes a lot of difference.

Similarly, I would like to suggest that Scripture is experience that has been thought out. The stories and other literary forms in the Bible are reflections on or distillations of human experience. The very process of transmission, first orally and then in writing, entails a thinking through of the experience that originally gave rise to the story, song, or teaching. We continue the tradition by adding our own reflection.

You can see it in today’s Gospel, the story of the transfiguration. Jesus takes three of his disciples up the mountain to pray, where his appearance is changed, his clothes becoming dazzling white. Moses and Elijah appear, a cloud then overshadows them, and a voice speaks words reminiscent of what Jesus heard at his baptism, this time obviously addressed to the disciples, “This is my Son, my Chosen, listen to him!”

Behind this story is an experience. It is what we have come to speak of as a religious experience. It is an experience of the sacred, when everything looks different, transformed in light. That the story has been carefully thought out is indicated by the details. For example, it takes place “about eight days after these sayings.” The sayings are Jesus’ prediction of his death, about which he has just spoken Now the experience takes place, not seven or nine but “eight days” after this prediction. Why eight? Because the eighth day is the first day, as “on the first day of the week Jesus Christ was raised from death.” The eighth day signals that this is a resurrection story. Suffering and death will come, but suffering and death are not the last word. The last word is the word of life, the promise of a new creation.

Or take the detail about climbing “the mountain.” Notice Luke does not say “a mountain.” It’s not just any mountain they are going to climb. They are not going for exercise. They are going to pray, and the mountain they are going up is the mountain of Jewish imagination, Mount Sinai, where Moses spoke with God and received the Ten Commandments.

Inspired by that encounter with God, there is no longer just any mountain, but every mountain becomes “the mountain,” where God again can be encountered. It is what the text means by prayer.

Suddenly two figures appear. They are Moses and Elijah, of course, because each stands for a decisive moment in Israel’s spiritual journey. Moses is the Lawgiver, Elijah, the model Prophet, and with them is Jesus, the Christ or Messiah. So we have something like “a Mount Rushmore of heaven.” And what they discuss is Jesus’ departure, the Greek word being “exodus.” So what the text is suggesting is that in Jesus there is a new exodus. As Moses led the Jewish people from slavery to freedom, so Jesus opens up the freedom of being God’s people to the gentiles. In Jesus’ life and death and resurrection is nothing less than a new exodus, not for one people but for all people.

All of this is to say that the experience that gave rise to this story has been carefully thought out, so much so that it symbolizes major themes of the Christian message. However meaningful these symbols may be, however, don’t lose touch with the experience itself. What has given rise to this story is a moment of awareness of God, when everything is lit up. There was a breakthrough in the consciousness of the three disciples. They saw and heard in a way they normally did not, what we might call extrasensory perception. What the story wants to tell us, which is what every religious experience wants to tell us, is that there is more than one kind of reality. There is the reality of space and time, what we normally perceive; but there is also what is beyond space and time, what is called the sacred, the realm of the divine.

I read recently that 43 percent of Americans have had some kind of mystical experience, the kind of experience that lies behind the story of the transfiguration. The title of this sermon is indicative of the growing interest in such experience. It is the title of James Redfield’s most recent work in new age spirituality. Author of The Celestine Prophecy and The Tenth Insight, Redfield’s work reflects the increasing interest in matters that once were considered the domain of the church and religion, but which now have broken out of all traditional boundaries. Things religious or spiritual now represent a huge market. Typical of the widening industry of books and tapes selling or packaging the sacred, The Celestine vision deals with such themes in chapters titled: “Experiencing the Mystical,” “Discovering Who We Are,” “Moving Toward a Spiritual Culture,” and “Visualizing Human Destiny.”

What Redfield and others write about is not new. The story of religion is the story about experiencing the divine. The Bible is not an argument for God. The Bible is stories about encountering God. It is not easy to speak, let alone write about such experiences, because they transcend normal categories of thought and description. Notice that Luke concludes his story by saying that the disciples who had experienced the transfiguration remained silent. Of course! What do you say after such an experience? So profound is the encounter that we speak about it with difficulty even to those with whom we are intimate. Awed silence is the customary response to the experience of the sacred.

Here is an attempt to describe a religious experience, a writing that comes not from the Bible but from the Christian tradition. It is from St. Augustine, who 1600 years ago wrote this. Listen to what he says:

How late I came to love you, O Beauty so ancient and so fresh, how late I came to love you! You were within me, yet I had gone outside to seek you. Unlovely myself, I rushed toward all those lovely things you had made. And always you were with me, I was not with you. All these beauties kept me far from you — although they would not have existed at all unless they had their being in you. You called, you cried, you shattered my deafness. You sparkled, you blazed, you drove away my blindness. You shed your fragrance, and I drew in my breath and I pant for you. I tasted and now I hunger and thirst. You touched me, and now I burn with longing for your peace.

This is transfiguration. It is coming to see that God is not a being out there someplace, but God is, as Bonhoeffer put it, “the beyond in our midst.” God is the depth of existence. Reality is more than what can be perceived with the five senses. Reality is more than what is on the surface. God is the beauty, the goodness, the truth in us and in all things. The issue is seeing it, seeing the world transfigured in the light of the divine. All is bathed in light, but we do not see it. The world is transparent to God, but we are blind. God is shining through all the things God has made. Do you see?

Naomi Wolf, a writer who has prided herself on her secular world view, disdaining anything religious, writes of encountering God, which changed her and the way she now understands her self and the world. It was an experience she did not seek or want. “It was upsetting,” she writes, “it shook me, it scared me, it created upheaval in my life, it was painful and unwelcome (as well as joyful and liberating).” What it has meant is that everything now is different. “As I’ve moved into a spiritual path, I’ve come to realize that every choice matters.” Words and thoughts, as well as actions, now have a significance they did not have before. Nothing is inconsequential. “I’m conscious that every single thing I put out is going to come back to me, and that every intention I have is going to manifest in the world. So I try to live more carefully now.”

We’re all climbing the mountain of God. The mountain is a symbol of the spiritual journey. It is likely we’re at different stages. That is why the season of Lent follows. The call to take on a spiritual discipline or practice for a specific period of time is to move us in our journey toward God. Sometimes we get stuck. The spiritual disciplines that Lent encourages are to help us get unstuck, to free us to move on.

The story of the transfiguration is given us just before we embark on Lent, given to remind us of the goal of our journey, the purpose of our living, which is to see the world in the light of God, to see other people not in racial categories or other stereotypes but to see every human being as a member of our own family, and to see the entire creation as an expression of the divine. And just as the story took place prior to Jesus’ decision to go to Jerusalem, where he would suffer and die, so we are reminded that whatever lies ahead for us, however difficult the way ahead, and when death itself comes, there is God, there is light and beauty and good, and because God is all is well. Be at peace, live carefully, that is, with care, and let the light of God light your way ahead.

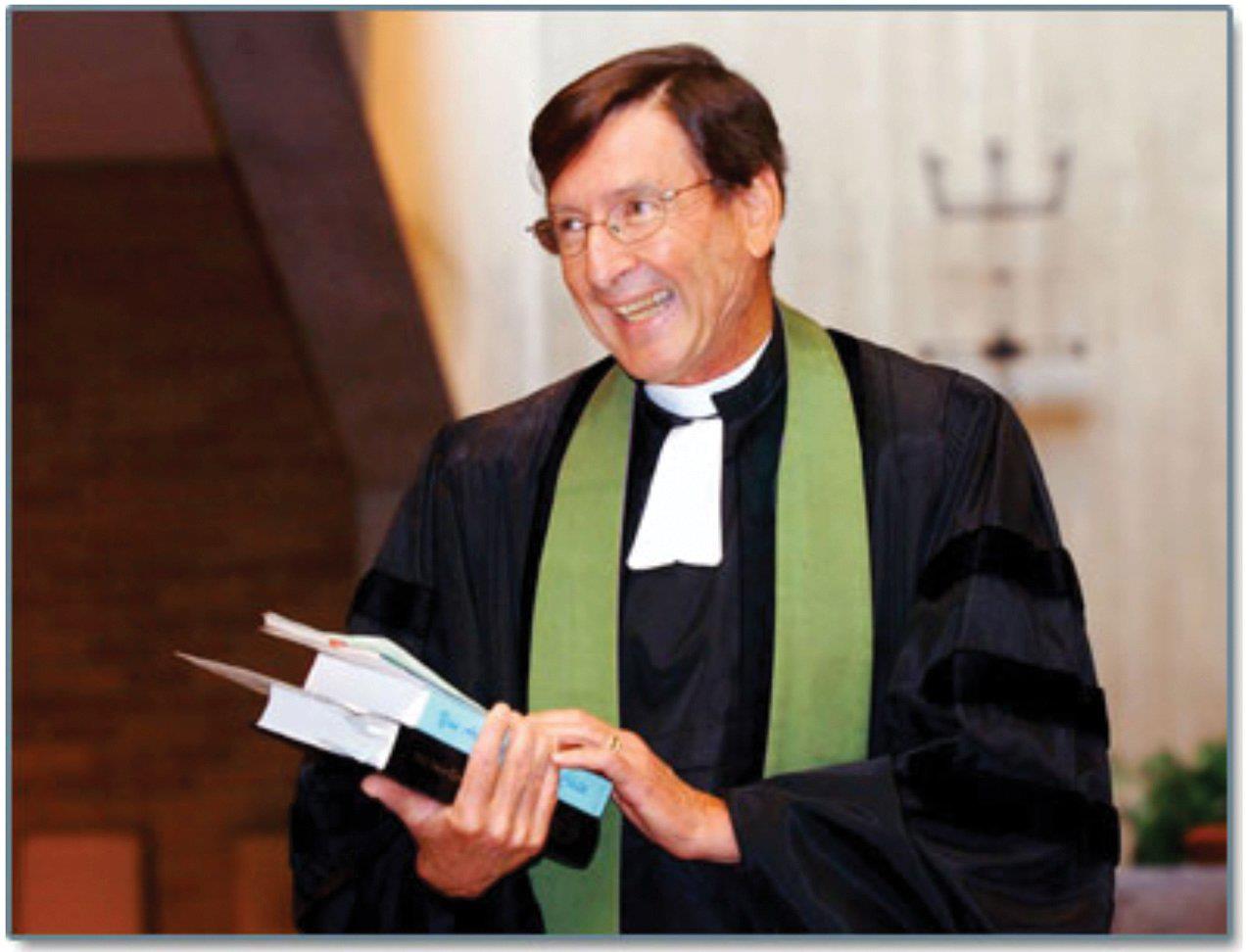

A leader in the Tulsa, Okla., interfaith community for more than three decades, Rev. Russell L. Bennett served as minister of Fellowship Congregational Church, the first mainline church in northeastern Oklahoma to openly welcome gay men and lesbians, for 36 years until his retirement in 2004. He helped found the Tulsa Interfaith Alliance in the 1980s and served as its president until 2006. A native of Los Angeles, he was raised in the Evangelical and Reformed Church, which merged in 1957 with the Congregational Christian Churches to form the United Church of Christ. He earned a master’s degree from Harvard Divinity School and a doctorate from McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago. His book You Are God’s Beloved Child contains writings from his years of ministry.