Here’s a powerful and moving story that has never received adequate historical coverage.

But it is a bit of history that forever changed the international struggle for gay rights and equality.

In the summer of 1968, one year prior to the Stonewall events, there was a little-reported West Coast bar action and police confrontation which served to galvanize gay activists in Los Angeles — and initiated a chain of events that directly led to the founding of the Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches (UFMCC).

Within months of this West Coast bar event, the Rev. Troy Perry held the first worship service of the UFMCC. Twelve worshipers gathered in his home in Huntington Park, California at 1:30 PM on October 6, 1968 — the first service of what today has become an international movement with more than 42,000 members and adherents in 15 countries, an annual income exceeding $15 million, and a powerful message of spiritual acceptance and affirmation for gays, lesbians, bisexuals and transgender persons.

Here is the story, as told by the Rev. Troy Perry, of the bar event and police confrontation that forever changed the face of GLBT spirituality:

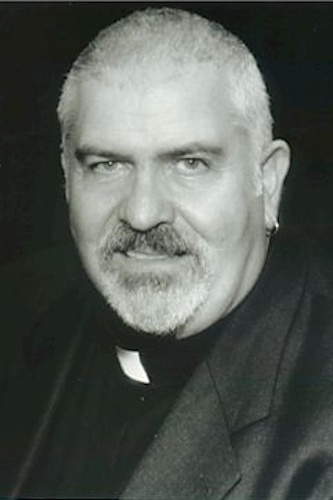

THE REV. TROY D. PERRY:

I went dancing on a summer evening in 1968. With me was a slender, very attractive man named Tony Valdez who was about twenty-two and married. Tony and I had known each other for several months. Our shared interest was that both of us liked going to The Patch, a very large gay dance bar in Wilmington, across the river from Long Beach and south of Los Angeles. I knew little about music, but Tony introduced me to LaBamba and taught me to enjoy fast dances. Popular were the Madison, the Monkey, and the Jerk, which were primarily massed male chorus lines with loud music and dance routines that rivaled sweaty calisthenics. Large, dramatically lit rooms were filled with cigarette smoke. People drank plenty of beer and behaved themselves better than many men and women in similar heterosexual establishments.

The difference, however, was twofold. One, we were gay, and two, the people with power in Los Angeles, for many homophobic reasons, endorsed vicious policies generally used against us. The police, without fear of retribution, sometimes murdered homosexuals, but more often laughed at us as they attempted to ruin our lives. Gay dance bars and overtly gay enterprises, no matter how well they were managed, rarely were able to stay in business as long as a year during the 1960s.

The Patch, widely known as a “groovy” bar, was running out of time. The manager was Lee Glaze, a tall, fast-speaking blond who said loud and often, “I may be a queen, honey, but I’m going to stand up for my rights.” When Lee said, “There’s something around here I’m allergic to, and it’s giving me an itch,” his words were an obvious signal that plainclothesmen had infiltrated the premises. A bar owner could be arrested for breaking police cover, but Lee never refrained. His reply to angry officers was, “You’re not here to do anything but harass us!”

The night Tony and I were dancing at The Patch was a dangerous evening. It seemed the music often stopped, either because uniformed police seemed to keep coming in and asking for people’s identification, or because Lee needed to use the band’s microphone to inform frightened customers that they had some constitutional rights and should not give in to gestapo tactics. Around midnight, many cautious customers had departed, but there were newcomers. Band music was loud. Scores of men were dancing as Tony went to the bar and purchased two beers, one for himself and one for me. When he returned to where I was standing, after about ninety seconds, a plainclothesman walked up to us and flashed a police badge into my face. “Follow me outside,” he demanded.

“Are you talking to me?” I asked.

“Not you, him,” snarled the officer, pointing to Tony.

Minutes later, Tony was charged with lewd and lascivious conduct, a standard but meaningless accusation used against homosexuals. It could mean anything, or nothing. In Tony’s case, he had been in my field of vision the entire time when he went to the bar, and if he had done anything illegal, he would have needed to be a magician. Or I needed to have my eyes examined.

Nevertheless, in spite of all protests, Tony was handcuffed and pushed into one of many squad cars that, for some irrational reason, were parked in front of the bar with their red lights flashing. Tony was hauled off to jail accompanied by a forty-year-old man named Bill who was also in handcuffs. Bill was accused of being lewd with Tony although the older man had merely slapped the latter on the rump in a casual fashion (exactly the way football players do).

Therefore a few infuriating minutes after the patently discriminatory arrests, Lee Glaze again took a microphone away from the band. He made a rousing speech that “Two people who are totally innocent have just been arrested,” Lee declared. “The cops are trying to put us out of business by keeping us frightened. I think all of us are familiar with the routine. We all know about harassment and entrapment. So let me tell you what we’re going to do. We’re going to fight! We have rights just like everybody else. Together we can beat the police-state tactics these lousy cops are using. We’ll all go get Tony and Bill out on bail, and we’ll carry bouquets of flowers to the jail, and we’ll stand in the light so everybody will know we’re no longer afraid! What do you say?”

Lee’s words thrilled me. There were still police around, listening and scowling, but he did not care. It was all a great revelation. In those moments I found courage within myself that I had never know existed. I suddenly realized that we, as gay people, could stand up and fight for our rights which had too long been denied.

I was already at the Harbor Jail when Lee arrived with a colorful procession of assertive, flower-bedecked homosexuals whom he led into the building. Imperiously, he announced to a shocked desk sergeant, “We are here to get our sisters out of jail!”

The moment was delicious, exciting, and certainly memorable. But it faded. We stunned the police, standard-bearers of our oppression, but time was on their side. As the hours of night marched toward dawn, our expensive array of flowers wilted. Yet we waited. When most of us had tired we began singing “We Shall Overcome” — over and over, louder with every refrain. The irritated police were not pleased, but Bill and Tony were released.

There was no celebration for Tony. He managed to make his way into my automobile before I saw the full extent of his mental agony. To say he was upset would be a colossal understatement. He was really upset! His clenched fists showed white knuckles. Moans of agony came from deep inside him. He refused to be touched by so much as a fingertip, and he resisted any word of consolation.

“Have you got anything to drink at your place?” Tony said while I was driving. I nodded, and twenty minutes later, as he sat at my breakfast table with early rays of the sun on his face, I let Tony pour his own glass of bourbon. When he had drunk a little of it, he was no less upset, but appeared calmer.

“Man, you know I never been arrested in my life for anything before,” he said, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand. “What am I going to do?” Before I could think of a reply, Tony began reflecting on something that had particularly galled him in jail. “You know,” he said, “there was a Chicano cop in there, talking to me through the bars, in Spanish. He called me a puto, a male whore, and he said he was going to call where I work and tell my boss there’s a puto working for him!”

“Tony, you just have to ignore — -”

“I tried to ignore! But do you know how it feels?”

“Yes.”

“No, Troy, you only think you know. You never been arrested! You don’t know how it is when the cell door bangs shut and you’re in their cage. I felt like a freak in a sideshow. Puto Latino!”

“Take it easy.”

“Do you know what everybody says about queers?”

“Come on, listen, it’ll work out all right.”

“No, it won’t,” growled Tony, standing. “I’m going to get a bus and go home. Nothing’s going to be all right. I don’t want to hear that crap. You live in an ivory tower. We’re just a bunch of dirty queers and nobody cares about dirty queers!”

“Somebody cares.”

“Who?”

“God cares.”

Tony had walked to the front door. He paused and uttered a terrible, painful laugh. “No, Troy,” he said, “God doesn’t care. What do you mean, `God cares.’ Be serious! I went to my priest for guidance when I was fifteen and he wouldn’t even let me come back to Sunday school. I guess he though I might contaminate somebody! He said I couldn’t be a homosexual and a Christian, so that was the end of church. And for me, in my religion, that meant the end of God!”

“You don’t need the church to speak to God.”

“I do.”

“Just get down on your knees and pray.”

“I can’t.”

“God will hear you.”

A look of increased sadness seemed to envelop Tony’s face. In his culture, religious exaltation was all-consuming, as it was in mine, but in a different way. He could not go to God without the intercession of a priest — but I could — because I knew it was possible to meet God anywhere.

“I’ll catch the bus,” my friend said.

Tony shut the door. As he walked out of my line of vision, I was still Pentecostal enough that I knelt down and urgently lifted my clenched hands in prayer. Somehow I knew I was approaching the culmination of my life, and I felt a building excitement. I went out of the house. The rest of the world still seemed to be sleeping as the bright sun arose.

A short time later, I lay on the bed in my room upstairs, tired from a night without rest, but nevertheless unable to sleep. I said, “Lord! You know I’ve prayed and I know you love me. You’ve told me that. I feel your Holy Spirit. What should I be doing? I can’t help thinking of Tony, alone, bitter, cut off from talking to you. I wish I could find a church somewhere that would help him. I wish there was church somewhere for all of us who are outcast.”

Suddenly, as if there was an electric spark in my head, I began asking myself, “What’s wrong with Troy Perry? Why are you waiting for somebody else?”

Then I prayed a little later that same morning, harder than ever before, and in the sort of talking I do, I said, “Lord, you called me to preach. Now I think I’ve seen my niche in the ministry. We need a church, not a homosexual church, but a special church that will reach out to the lesbian and gay community. A church for people in trouble, and for people who just want to be near you. So, if you want such a church started, and you seem to keep telling me that you do, well then, just let me knew when?”

Whereupon, I received my answer to an impossible dream. A still, small voice in my mind’s ear spoke, and the voice said, “Now.”

The entire story of the founding and expansion of UFMCC is told in the book, Don’t Be Afraid Anymore: The Story of Reverend Troy Perry and the Metropolitan Community Churches, authored by the Rev. Troy D. Perry and published by St. Martin’s Press.

An American religious leader and gay and human rights activist, Rev. Troy Deroy Perry Jr. is founder of the Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches. On June 28, 1970, with two friends, Morris Kight and Bob Humphries, he founded Christopher Street West to hold an annual Pride parade that is now the world’s oldest. His books include the autobiography The Lord is My Shepherd and He Knows I’m Gay and a sequel titled Don’t Be Afraid Anymore, plus Profiles in Gay and Lesbian Courage and 10 Spiritual Truths For Gays and Lesbians* (*and everyone else!). He was a contributing editor for the book Is Gay Good?