For you created my inmost being; you knit me together in my mother’s womb. I praise you because I am fearfully and wonderfully made; your works are wonderful, I know that full well. (Psalm 139:13-14 NIV)

Society has a problem with gender differences. People whose genders are not considered “normal” are forced to bear the weight of the grip that the cisgender heteronormative has on all our lives.

In ancient Judaism, there was a range of gender identities: Male characteristics, female characteristics, androgynous (both characteristics), and tumtum (not definitely both characteristics). Also, in ancient Judaism, it was understood that one’s gender identity evolved over time. For example, someone born male later in life becomes a eunuch (saris), or someone born female later in life becomes “man-ish” (aylonit)

The Bible is replete with stories of various gender identities in God’s people; these biblical stories affirm that we all are wonderfully made — and also our God-given right to live those identities out loud.

Today’s college students embrace and live out loud these various genders. The various gender-inclusive pronouns acknowledge and respect intersex, transgender, nonbinary, and gender-nonconforming people. Like so many colleges, my alma mater is wrestling with these issues.

In February, Wellesley College students voted overwhelmingly to pass a gender inclusivity ballot question allowing transgender men and nonbinary people who were assigned male at birth to be eligible for admission. The nonbinding referendum also requested that the language used at the college be inclusive of its nonbinary and transgender students, thereby bridging the communication gap over gender-inclusive language between the administration and the student body.

In response, the college agreed to train and teach its staff and faculty about gender identity and pronoun use but drew the line at admitting trans men, flatly stating that “there is no plan to change Wellesley’s admissions policy or its mission as a women’s college.”

Wellesley is considered one of the premier women’s colleges in the country, with noted alumnae including Madame Chiang Kai-shek (First Lady of the Republic of China), filmmaker Nora Ephron, television journalist Diane Sawyer, Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, and Hilary Clinton. But as with the other few remaining women’s colleges in this 21st century, Wellesley will have to rethink its mission — “to provide an excellent liberal arts education to women who will make a difference in the world” — in a society that no longer adheres to the traditional gender binary of male and female.

If it seems as though more people are identifying as transgender or nonbinary, it’s because they are. According to a 2022 Pew Research Center poll, American young adults under 30 are more likely to identify as transgender or nonbinary than older adults. In addition, 44 percent of Americans now say they personally know at least one person who is transgender, and 20 percent know someone nonbinary, underscoring that these are not invisible demographic groups in society any longer — especially on college campuses.

College should be a safe space and an atmosphere that engenders a positive sense of self for all students, which is the basis of educational achievement and personal growth. But too often, transgender students on college campuses must cope with being misgendered, and non-binary students must cope with the annoyance of gender-binary labeling.

I cannot imagine what it must feel like for transgender and nonbinary students to evolve into their authentic selves at Wellesley and yet not be acknowledged or affirmed — and how the college’s use of the words “women” and “alumnae” can leave them feeling that their individual identities are not embraced.

As an African-American lesbian, I do know what it is like to feel uncertain in a space as an individual and part of an identity group — and also to be made invisible or erased because of intentional or unintentional institutional and cultural biases, as in the Black church and black community.

I also am a Wellesley graduate. I was a student there when it was academically and socially unsafe to be openly lesbian. Because of both intentional and unintentional institutional and cultural biases, I stayed closeted for fear of stigmatization and discrimination. I didn’t want to be disrespected or treated as an unvalued and unwelcome part of the college community. I remember those years as if they were yesterday, albeit decades ago.

When I returned to Wellesley years later as a head-of-house, much had changed since my undergraduate years. For example, the freshman class were now called first-year “students,” and house mothers, who were administrators of dormitories, were now called heads-of-house (which most other schools refer to as resident assistants).

Having African-American heads-of-house was no longer inconceivable because I was one — and so too was Michelle Porche.

By 1991, when I was named head-of-house at Stone-Davis dormitories, the country had evolved further in understanding the fluidity of gender identities and sexual orientations, and Wellesley was taking a giant step in hiring two out lesbians to run dormitories: Porche, a graduate student at the Harvard School of Education, and me, a doctoral student at Harvard Divinity School. Porche arrived on campus with her white live-in partner, amid some disdain for interracial couples. I came with my mixed-breed dog, Heaven.

Our hiring was controversial. An article in the Campus Life section of The New York Times that year said:

To the administration, it was a “great step forward” to hire a lesbian with a live-in partner as a head-of-house, but not a good idea to assign her to a dorm with a lot of first-year students.

But Wellesley survived our hiring, the Board of Trustees didn’t disband, and alums who had threatened to withhold their donations didn’t.

The idea of admitting trans men is controversial too. However, one of Wellesley’s values is gender equality; its own website states: “As a women’s college, we have always been committed to gender equality as foundational to societal progress.”

In an open letter to the Wellesley community titled “Affirming our mission and embracing our community,” President Paula A. Johnson wrote:

Wellesley is a women’s college that admits cis, trans, and nonbinary students — all who consistently identify as women. Wellesley is also an inclusive community that embraces students, alumnae, faculty, and staff of diverse gender identities. I believe the two ways of seeing Wellesley are not mutually exclusive. Rather, this is who we are: a women’s college and a diverse community.

Wellesley was founded in 1870 — five years after the Civil War and 50 years before women were allowed to vote — with the understanding that women, as defined in that era, were a marginalized group and should have access to higher education. As women, we are a marginalized group still today. And so too are transgender and nonbinary students.

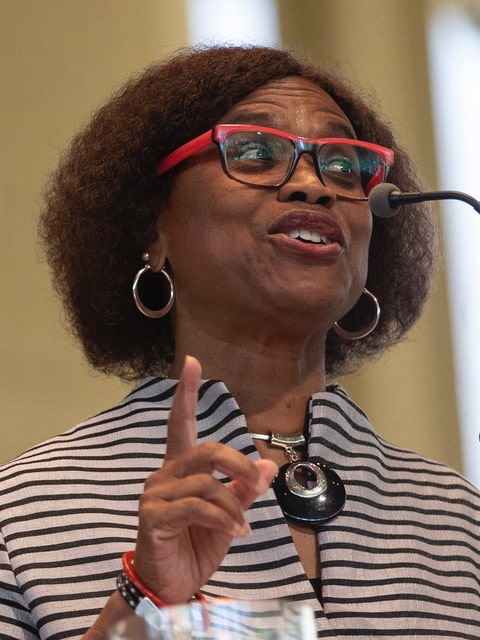

Public theologian, syndicated columnist and radio host Rev. Irene Monroe is a founder and member emeritus of several national LBGTQ+ black and religious organizations and served as the National Religious Coordinator of the African American Roundtable at the Center for LGBTQ and Religion Studies in Religion at Pacific School of Religion. A graduate of Wellesley College and Union Theological Seminary, she served as a pastor in New Jersey before studying for her doctorate as a Ford Fellow at Harvard Divinity School and serving as the head teaching fellow of the Rev. Peter Gomes at Memorial Church. She has taught at Harvard, Andover Newton Theological Seminary, Episcopal Divinity School and the University of New Hampshire. Her papers are at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College’s Research Library on the History of Women in America.