There’s still a difference between accepting and affirming

Last month, United Methodist Church delegates voted to repeal the denomination’s long-held exclusionary stance toward its LGBTQ+ members in church doctrine, polity, and social standing.

The news was received with mixed feelings — cheers and tears.

“We have been Methodists since 1917 in the oldest black section of Houston,” Harold Cox, an openly African-American gay male from Boston, shared with me. “I’m sad because the United Methodist Church is my family’s business.”

Cox comes from a supportive and long family line of Methodist ministers — three uncles and his father, firstly of Black Methodist Churches (before white Methodist Churches merged with them in 1968 to become the UMC).

Cox, who is also a “PK,” (pastor’s kid), added: “I’m sad the church couldn’t find a way in their differences to find a way to reconcile.”

He went on to share a little history with me:

Prior to 1968, my family was part of the black church that was an offshoot of the white church. They had their own bishops and administrative church structure. The merger in 1968 changed all of this. Of course we lost out. There used to be to be seven or eight black district superintendents. After the merger, there was one.

Defrocked and excommunicated clergy

For me, this news is bittersweet. My heart aches at the number of my United Methodist clergy friends through the decades who have been defrocked — either for being LGBTQ+ or for supporting LGBTQ+ rights.

For example, in 1999, Rev. Jimmy Creech, a heterosexual ally, was defrocked for performing same-sex unions. In 1997, Creech officiated at a same-sex union for a lesbian couple in Omaha. In 1998, the Judicial Council of the United Methodist Church ruled that Creech violated church law. On the eve of his trial, he officiated a recommitment ceremony for a gay male couple in NC.

The Advocate magazine that year asked him why he continued to marry same-sex couples, knowing the church’s position. Creech rightly said:

A cultural prejudice… has been institutionalized in the church. The position of the church is wrong; it’s unjust. It’s discriminatory. It isolates a part of our population, part of the brothers and sisters of the human family. It denies their humanity, considers their own humanity to be somewhat unnatural or immoral or sinful.

During that era, however, not all UMC congregations shut their doors to LGBTQ+ parishioners. I was instrumental in Union United Methodist Church, a predominantly African-American church in Boston’s South End (once the epicenter of the city’s LGBTQ+ community) becoming a Reconciling Congregation, the first in New England. It is the one institution that was least expected to be lauded among LGBTQ+ people of African descent, given the Black church’s notorious history of homophobia. When its pastor came out at the General Conference in 2016 to move the global church body’s moral compass against its anti-LGBTQ+ policies, UUMC was in full support.

Disaffiliation as a means of peace

The bittersweetness of moving the UMC to repeal its theological stance on LGBTQ+ issues is that approximately one-fourth of the denomination’s churches have disaffiliated. Since 2019, 7,600 churches have left. In January 2020, before COVID, the church had thoughts of splitting. I had hoped that during COVID, the church would have time to reflect as a church body on its decision.

“Maybe it’s a separation that needs to happen,” Cox told me. “Fifty years is a long time to be fighting.”

For decades, the UMC struggled to adopt a policy that fully included its LGBTQ+ parishioners, clergy, and all the spiritual gifts we bring to the church.

Because of the ongoing tension and seemingly intractable arguments between conservative and progressive factions of the UMC about how the church should handle LGBTQ+ ministers and parishioners, the Council of Bishops devised three plans developed by the Commission on a Way Forward at the 2019 General Conference Special Session in St Louis, Mo.

“The Commission’s purpose was never to arrive at uniformity of thought among its own members or to design the shape the church should take in the future,” the report explained. “The purpose has been to help the Council of Bishops and the General Conference to do this work of decision-making.”

In the hope of avoiding a schism, the Council of Bishops recommended a “One Church Plan” that would grant individual ministers and regional church bodies the decision to ordain LGBTQ+ people as clergy and to perform LGBTQ+ weddings. It was believed that such a decision on a church-by-church and regional basis would reflect the diversity and affirm the different churches and cultures throughout the global body of the UMC.

The One Church Plan, however, was one of three proposed plans by the UMC’s Commission on a Way Forward. The others include the Traditionalist Plan and the Connectional Conference Plan, both exclusionary to LGBTQ+ parishioners.

The One Church Plan would excise the offensive and controversial language targeted at LGBTQ members from the Book of Discipline and replace it with a more compassionate, accurate, up-to-date, and contextualized language about human sexuality in support of the mission and all its parishioners. Also, the One Church Plan would uphold religious freedom and thereby safeguard those clerics and conferences unwilling to ordain or marry us because of their theological convictions.

However, the UMC still continues to be contradictory in its policies concerning LGBTQ+ worshippers. For example, UMC states that we have and are of the same sacred worth as heterosexuals and that the church is committed to the ministry of all people regardless of gender identities and sexual orientation. But the church also views queer sexualities as sinful. The Book of Discipline states that sexuality is “God’s good gift to all persons” and that people are “fully human only when their sexuality is acknowledged and affirmed by themselves, the church, and society.” This rule, however, is not applicable to LGBTQ+ people.

It must be noted that while the UMC has repealed its stance on LGBTQ+ clergy and removed its condemnation of LGBTQ+ sexualities and gender expressions from its church law and doctrine, the change does not offer a full-throated endorsement of same-sex marriages. It removes their prohibition.

A smaller church

“The United Methodist Church was an important vehicle supporting colleges and hospitals in my life. That is important,” said Cox. “With a smaller church, it’s harder to care for and continue with those activities.”

Although the UMC is a smaller body, LGBTQ+ Methodists can now be fully out in the church. The hope is that many of the disaffected will return. Cox won’t be one of them.

Harold Cox is now an Episcopalian.

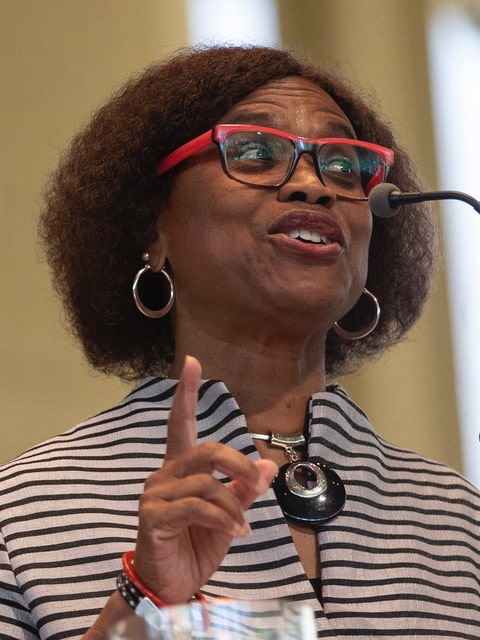

Public theologian, syndicated columnist and radio host Rev. Irene Monroe is a founder and member emeritus of several national LBGTQ+ black and religious organizations and served as the National Religious Coordinator of the African American Roundtable at the Center for LGBTQ and Religion Studies in Religion at Pacific School of Religion. A graduate of Wellesley College and Union Theological Seminary, she served as a pastor in New Jersey before studying for her doctorate as a Ford Fellow at Harvard Divinity School and serving as the head teaching fellow of the Rev. Peter Gomes at Memorial Church. She has taught at Harvard, Andover Newton Theological Seminary, Episcopal Divinity School and the University of New Hampshire. Her papers are at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College’s Research Library on the History of Women in America.