Whether it’s National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, World AIDS Day or any other day set aside for us to confront this epidemic, one sad fact remains startlingly true: HIV/ADS remains an overwhelmingly Black disease in the United States.

I remember reading a report this time last year that drew on statistics compiled by the U.S. Office of Minority Health; here is the executive summary, if you will:

Although Black/African Americans represent almost 13 percent of the U.S. population, they account for 42.1 percent of HIV infection cases in 2019.

- In 2019, African Americans were 8.1 times more likely to be diagnosed with HIV infection, as compared to the white population.

- African American males have 8.4 times the AIDS rate as compared to white males.

- African American females have 15 times the AIDS rate as compared to white females.

- African American men are 6.4 times as likely to die from HIV infection as non-Hispanic white men.

- African American women are 14.5 times as likely to die from HIV infection as white women.

In a POZ magazine poll (“Are you participating in any World AIDS Day 2022 events?“) I took just two months ago, the instant results I saw were that 20 percent said yes, 20 percent said “I don’t know,” and 60 percent said no.

Designated in 1988 by the World Health Organization, World AIDS Day is meant for us to pause and reflect on the magnitude of the devastating effect this disease continues to have on domestic and global communities. Much of the focus still is on developing countries.

But with African Americans still disproportionately affected by this epidemic, it remains heavily concentrated in urban enclaves such as Boston, Detroit, New York, Newark, Washington, D.C. — as well as in the Deep South.

Massachusetts, where I live, is a world-renowned medical hub known for its HIV/AIDS research and support systems, but the outcomes remain stubbornly grim. In 2019, according to a University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School report titled “Burden of HIV & AIDS Amongst the Black Community in Massachusetts as Compared to the General Population,” African Americans comprised 7.3 percent of the population but represent 32 percent of people newly diagnosed with HIV.

This means that the rate of African American males living with HIV is 5.2 times of white males, and the rate of African American females living with HIV is 22.7 times that of white females. African Americans who contract HIV are still more likely to die from it than members of other racial groups.

But this data doesn’t reflect the wave of recent African diasporic immigrants of the last decade coming from the Caribbean Islands and Africa itself. This demographic group is overwhelmingly underreported and underserved — for fear of not only deportation but also of homophobic insults and assaults from their communities.

So why is HIV/AIDS still an overwhelmingly Black disease in the United States?

There are many persistent social and economic determinants contributing to the high rate of the epidemic in the African American community: Poverty, homelessness, health care disparity, the prison-industrial complex, and violence — to name a few. And while we know that the epidemic moves along the fault lines of race, class, gender, and sexual orientation, it’s also true that homophobia, stigma and the Black church continue to be barriers to ending the epidemic.

However, the most significant obstacle is still systemic racism.

In 2021, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control declared racism a serious public health threat and warned of its impact on health outcomes. The White House sent a similar shockwave that same year with this matter-of-fact acknowledgment in its National HIV/AIDS Strategy for 2022-2025 of the role of racism in hindering progress against the epidemic:

The Strategy recognizes racism as a public health threat that directly affects the well-being of millions of Americans. Over generations, these structural inequities have resulted in racial and ethnic health disparities that are severe, far-reaching, and unacceptable.

They’re not alone. The World Health Organization’s theme for World AIDS Day 2022 was “Equalize,” and HIV.org declared theirs as “Putting Ourselves to the Test: Achieving Equity to End HIV.”

I hope the POZ poll is incorrect and that many did in fact participate in a World AIDS Day event. But I feel assured that no matter who did or didn’t participate on that day, Black lives living with HIV/AIDS are beginning to matter.

We can end AIDS — if we end the inequalities which perpetuate it. This World AIDS Day, we need everyone to get involved in sharing the message that we will all benefit when we tackle inequalities. To keep everyone safe, to protect everyone’s health, we need to “Equalize.” (UNAIDS Executive Director Winnie Byanyima)

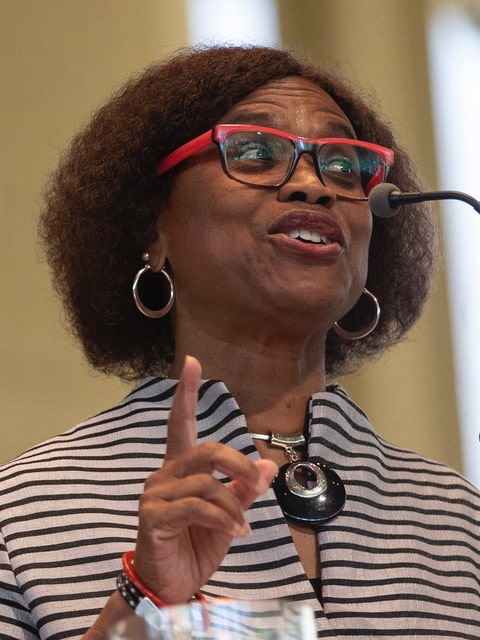

Public theologian, syndicated columnist and radio host Rev. Irene Monroe is a founder and member emeritus of several national LBGTQ+ black and religious organizations and served as the National Religious Coordinator of the African American Roundtable at the Center for LGBTQ and Religion Studies in Religion at Pacific School of Religion. A graduate of Wellesley College and Union Theological Seminary, she served as a pastor in New Jersey before studying for her doctorate as a Ford Fellow at Harvard Divinity School and serving as the head teaching fellow of the Rev. Peter Gomes at Memorial Church. She has taught at Harvard, Andover Newton Theological Seminary, Episcopal Divinity School and the University of New Hampshire. Her papers are at the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College’s Research Library on the History of Women in America.